|

High-density lipoproteins (HDL) are also known as “good” cholesterol. These particles help to remove cholesterol from the body by carrying it from the rest of the body to the liver, where it’s eliminated. There are a number of ways to help keep your HDL levels in the optimal zone, including exercising, quitting smoking, and taking supplements. There are also certain foods that, in correlation with exercise, can help to raise your HDL levels (and/or improve the ratio of your HDL to LDL levels). What do these foods have in common? High in healthy fats: Foods such as fatty fish, nuts, and seeds are great dietary sources of omega-3 fatty acids. Omega-3s are known for their heart-healthy benefits, but they also have the power to raise HDL levels.3,4 High in antioxidants: Known for the role they play in supporting a healthy immune system, antioxidants help to protect our bodies from the damage caused by oxidative stress. Foods high in antioxidants such as berries, grapes, and green tea have an added benefit: A higher antioxidant level is associated with improved HDL numbers.5 HDL is actually an antioxidant itself, helping to prevent the oxidation of lipids on LDL particles and helping to remove free radicals.6,7 So which foods should you add to your next grocery list? Conclusion

So if your healthcare practitioner has suggested you increase your HDL levels to help optimize your health, consider adding one or more of these foods to your daily diet! References: 1. Zhou Q et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(5):4726-4738. 2. Brown L et al. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(1):30-42. 3. Franceschini G et al. Metabolism. 1991;40(12):1283-1286. 4. Yanai H et al. J Clin Med Res. 2018;10(4):281-289. 5. Kim K et al. Nutrients. 2016;8(1):15. 6. Xepapadaki E et al.. Angiology. 2020;71(2): 112-121. 7. Brites F et al. BBA Clinical. 2017;8:66-77.

0 Comments

By Melissa Blake, ND

Modern-day living has granted us access to an abundance of both food and artificial light, contributing to an endless opportunity for food production and consumption. The opportunity for overindulgence can lead to a number of health issues, including changes in sleep, mood, and energy, unwanted weight gain, heart conditions, memory issues, and digestive complaints. The circadian diet offers a solution to these negative outcomes and is basically a way of aligning intermittent fasting with your circadian rhythm that takes into account not only what you eat, but when you eat. What is the circadian diet? While similar to intermittent fasting, the circadian diet divides a 24-hour day into two windows—one window when food is consumed and the other spent fasting (no food, only water). The circadian diet emphasizes eating in sync with the body’s natural tendencies and instincts. This means eating during daylight hours during a window that is approximately 12 hours long and falls somewhere between sunrise and sunset, with evidence suggesting the earlier the eating window closes, the better.1 Eating in this way, with an emphasis on dietary timing, can help support the body’s natural circadian rhythm and contribute to overall health and wellness.1 The benefits of the circadian diet The circadian diet, in part due to a positive impact on circadian rhythm, contributes to substantial benefits on sleep and metabolic health. This often means better energy, fewer cravings, blood sugar control, improved digestion, and weight loss.1 When done properly, the circadian diet is a safe and effective way of eating, and modifications can be made to suit almost any lifestyle, cuisine, or dietary preferences. A sample day on the circadian diet Morning routine: A day on the circadian diet involves more than just food. It starts with waking at a consistent time, ideally with the sun. After you wake, drink water or herbal tea to help meet your hydration needs. Follow that up with some gentle stretching or movement to help get the blood flowing and energize the body. Try to get outside within one hour of waking in order to help optimize your body’s internal clock. Break-the-fast: Next, begin the 12-hour eating window within two hours of waking by literally breaking the fast with a well-balanced meal that includes protein, fruit, vegetables, and good-quality fat. Aim to consume most of your calories earlier in the day, with a smaller meal to close the eating window. Ideally, you’ll want to stop eating two or more hours before bedtime in order to allow the body sufficient time for digestion. “Aim to consume most of your calories earlier in the day, with a smaller meal to close the eating window. Ideally, you’ll want to stop eating two or more hours before bedtime in order to allow the body sufficient time for digestion.” Close the window: During the fasting window, which ideally starts early in the evening, drink water and herbal tea to stay hydrated. Consider a gentle movement routine and other calming activities to promote sleep, such as journaling, light reading, and breathing practices. Another important aspect of the circadian health diet involves limiting technology, especially during the evening hours. Shut off all screens and try to reduce your exposure to light for at least one hour before bed to reduce any potential disruptions to sleep patterns.2 Finally, ensure you have a dark, cool, and comfortable sleep space combined with a consistent bedtime to help round out your day. Things to consider with the circadian diet Initially, people may experience hunger during the fasting period of the circadian diet, especially those who struggle with nighttime eating or blood sugar control. These issues generally can be avoided if the fasting period is introduced slowly over a period of time, with gradual increases to the fasting window. Many people have predetermined thoughts about food and it can be helpful to clean that slate and unlearn what you think you know about food. For example, avoid categorizing food as “good” vs. “bad” or even “breakfast” vs. “supper” foods. Aim to become more adventurous in the kitchen – this could mean eating chicken and salad for breakfast or a hearty bowl of lentil soup. Following a circadian diet means listening to your body and its needs. This can be a challenge if you struggle with unhealthy food cravings or are new to a whole foods way of eating. Ask for help and take it slow. If you have a significant medical concern or if you’re unsure where to start, consider speaking with a knowledgeable healthcare provider who can help support you with a personalized plan. Every step, even if it seems small, counts. The key is what you choose to do every day. Daily habits and routines have the most significant impact on circadian rhythm and offer an opportunity for anyone to optimize circadian health, contributing to better overall health and wellness. References: 1. Zheng D et al. Trends Immunol. 2020;41(6):512-530. 2. Aulsebrook AE et al. J Exp Zool A Ecol Integr Physiol. 2018;329(8-9):409-418. by Bianca Garilli, ND

When doctors measure our cholesterol, they look at the vehicles that carry it in our blood—which gives them a clue what our body is doing with that cholesterol. The two most common and well-known vehicles are low-density lipoproteins (LDLs) and high-density lipoproteins (HDL). LDL is frequently referred to as “bad cholesterol,” while HDL is deemed “good cholesterol,” although it is now known that understanding cholesterol and its effects on the human body are much more complicated than this simplified breakdown. Nonetheless, it’s still very important to maintain adequate levels of the “healthy” HDL. So if you’ve been told that you need to increase your HDL levels to optimize health, keep reading to discover several HDL-boosting tips. Tip 1: Exercise! It’s true! Exercise is not just great for improving body composition, balancing blood sugar, losing weight and feeling happier, it’s also been shown to be associated with a healthier lipid and lipoprotein profile, thus lowering the risk for heart health problems.1,2 In a study comparing well-trained soccer players to sedentary controls, researchers found the average HDL-C levels in the athletes was 12.5% higher than in the nonexercising controls.2 This is important when considering that HDL can be compared to a “dump truck” for the cell; it gathers excess cholesterol left in the artery walls and carries it to the liver for disposal (breakdown and excretion).3 Too little HDL can lead to excess plaque buildup and subsequent risk of cardiovascular issues.2 One medical organization notes that benefits of exercise can be seen in as little as 60 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise per week, while a meta-analysis that included 25 studies indicates it may be closer to 120 minutes of weekly exercise to experience an HDL benefit.4,5 This meta-analysis concluded that it was the exercise duration rather than intensity or frequency that resulted in best benefits.5 And, in fact, it seems that more is better: “Each 10-minute increase in exercise duration corresponded to an approximately 1.4-mg/dL net increase in HDL-C level.”5 Tip 2: Take targeted nutritional supplements Nutraceuticals have become an indispensable and regular part of supplementing healthy living these days. Known for their vast array of health benefits, omega-3 fatty acids have been shown to also support healthy HDL levels.6 Omega-3s have two broad categories: eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), both downstream metabolites of the well-known class of anti-inflammatory promoting omega-3s called alpha-linolenic acid or ALA.7 Studies indicate it is the DHA that is most effective in improving HDL levels with one study showing a 4.49 mg/dL increase in HDL when subjects were given DHA compared to placebo subjects not given DHA.6 Tip 3: Stop smoking It’s been well-established that smoking is detrimental to health and, in particular, is a significant risk factor for cardiovascular health problems.8,9 Smoking has been shown to reduce levels of HDL and other underlying causes that lead to an increased risk of heart issues.9 The good news? When someone quits smoking, a reversal in HDL levels can be seen with the recently smoke-free person’s cardiovascular risk soon approaching that of the long-term nonsmoker.10,11 In summary, higher serum levels of HDL are positively associated with a lowered risk for the development of cardiovascular disease.12 On the flip side, a suboptimal level of HDL may increase an individual’s risk for cardiovascular issues, in both men and women.13 Keeping HDL levels within their optimal range is important. Here are three things you can do right away to ensure your HDL levels are moving in the right direction:

References:

Onions are an overlooked vegetable. Whether they’re being sautéed for a soup, sliced for a burger, or pickled for a salad, onions rarely steal the show of a meal, although they often inspire a sob story.

Onions are most known for their pungent flavor, not necessarily their nutritional value. Their white flesh (even in red onions) isn’t always perceived as being as nutritious as vibrantly colored vegetables like kale, broccoli, or beets. But that’s no reason to snub onions. Although some onion varieties are lacking in color, onions in general are one of the highest natural sources of a powerful flavonoid: quercetin.1 What is quercetin? Quercetin is a flavonoid, which is a chemical compound found in plants. In addition to onions, quercetin is also found in many other fruits and vegetables like capers, asparagus, and apples, as well as tea and red wine.1 A single serving of onions is considered to be one medium onion, which contains around 52 milligrams (mg) of quercetin.2 But most people tend to not eat a whole onion in one sitting (unless they really like onions), so you’re probably not getting quite that much quercetin when you eat onions. Even with all these natural sources of quercetin, it’s estimated that most people following a typical Western diet (think higher in simple sugars and animal products and lower in produce) only get 0 to 30 mg a day.1 That’s not a lot, considering research shows that some of quercetin’s health benefits are reached at supplemental intake levels, not from a food source, of 500 to 1,000 mg per day.3 Quercetin and health Quercetin is one of the most studied dietary flavonoids and is associated with multiple health benefits. Two of this compound’s most notable benefits are supporting heart health and protecting against oxidative stress. Heart health: Quercetin plays a positive role in supporting healthy blood pressure and endothelial health.4 The endothelium is the thin layer of cells lining the body’s blood vessels and heart. It is considered an active organ in the body as it helps control when blood vessels relax or constrict.5 Protection against oxidative stress: Everyone undergoes oxidative stress, which is caused when there is an imbalance of harmful free radicals, which damage cells and tissues. This process happens inside the body, so although you may not feel immediate effects from oxidative stress, it can affect both health and the immune system over time. Antioxidants can help quell some of that stress. And since quercetin acts as a free radical scavenger and supports antioxidant processes, it’s especially good at this.3 Getting the most quercetin out of onions Because these health benefits are mainly seen at higher levels of quercetin intake, it’s important to maximize what you can from the diet. Here’s how you can get the most quercetin when eating onions.

Onions are a rich, natural source of the flavonoid quercetin. High intakes of quercetin are associated with cardiovascular benefits and oxidative stress protection. However, quercetin is not a “magic bullet” to health. Instead, focus on eating a plant-forward diet with lots of produce and know that onions, albeit smelly, are a healthful choice. References:

Every BODY and every age have unique nutritional needs. However, with every stage of life, there are common nutritional inadequacies that women are most likely to experience. Learn what supplements are best for YOU! 20s You may find yourself strapped for time and cash during these exciting transitional years, which could result in an unbalanced diet. What supplements should you consider taking?

In your 30s, you may be expanding your family and/or career, so you need all the energy you can get!

Your 40s are filled with possibilities; whether you are starting a new business, climbing the corporate ladder, juggling older kids, or welcoming a new addition, women in their 40s are thriving!

Your 50s and beyond can be a great time to reconnect with yourself and maybe your spouse too. Make sure to support all the amazing years ahead of you with high-quality supplements.

References

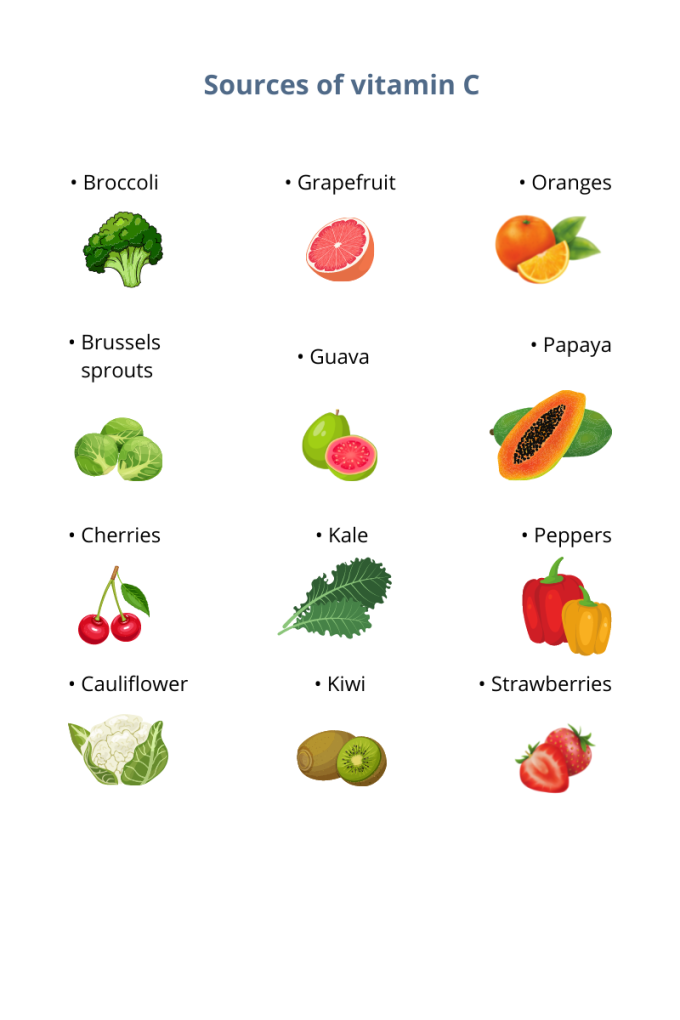

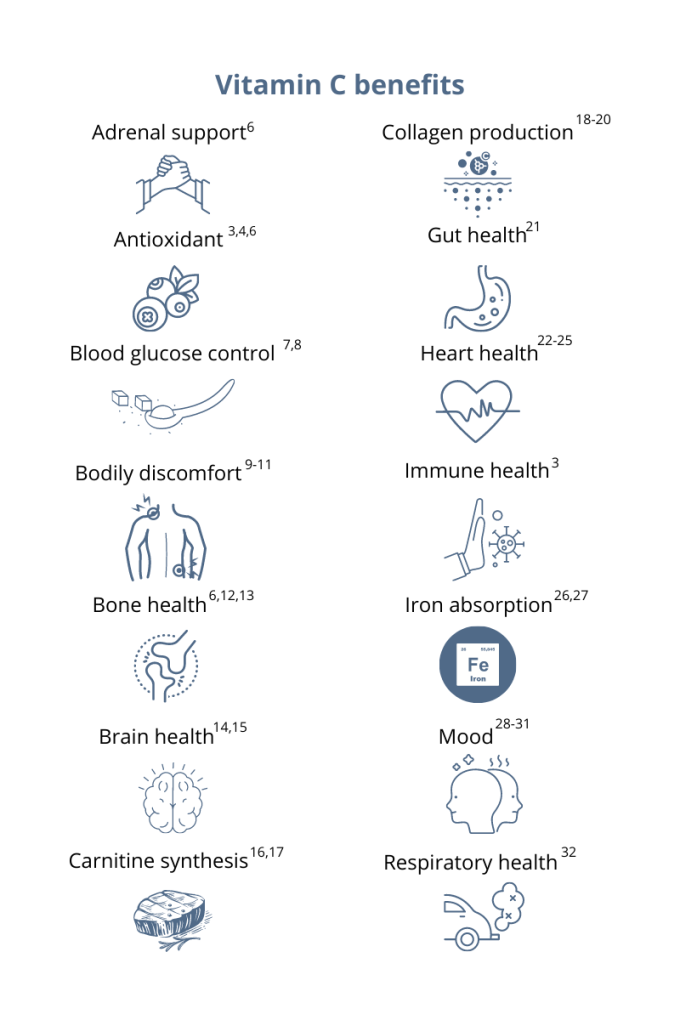

You’ve probably heard that vitamin C supports your immune system. This essential micronutrient seems to be everywhere! And it’s a good thing because, unlike most mammals, humans can’t synthesize vitamin C on their own.1 Also, vitamin C is water-soluble, which means the body quickly loses this essential vitamin through urine, so it’s important to make vitamin C a daily part of your diet.1 Having extremely low levels of vitamin C for prolonged periods can result in scurvy, a historical disease linked to pirates and sailors who faced long journeys at sea without fresh fruits and vegetables. While cases of scurvy in the United States are rare, a recent study reported that 31% of the US population are not meeting the daily recommended intake of vitamin C.1 Greater than 6% of the US population are severely vitamin C deficient, while low levels of vitamin C, associated with weakness and fatigue, were observed in 16% of Americans.2 As a whole, 20% of the US population showed marginally low levels of this essential micronutrient.2 How much vitamin C do I need?The US recommended daily dietary allowance of vitamin C is 75 mg for women and 90 mg for men.3 Experts recommend an estimated 200 mg of vitamin C daily for favorable health benefits.4 Adults can take up to 2,000 mg of vitamin C per day; however, high doses of vitamin C may cause diarrhea, nausea, and stomach cramps.5 Due to the varying health needs of individuals, it’s always a good idea to work with your healthcare practitioner to ensure that you are getting the right amounts of micronutrients in your daily diet. Where can you find this marvelous, multifaceted micronutrient? Ready to add vitamin C to your daily regimen? Talk to your healthcare practitioner about how much would be right for you.

References: 1. Granger M et al. Adv Food Nutr Res. 2018;83:281-310. 2. Schleicher RL et al. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(5):1252-1263. 3. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminC-HealthProfessional/. Accessed August 3, 2021. 4. Frei B et al. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2021;52(9):815-829. 5. Hathcock JN et al. AM J Clin Nutr. 2005;81(4)736-745. 6. Ashor AW et al. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2017;71(12):1371-1380. 7. Mason SA et al. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;93:227-238. 8. Chen S et al. Clin J Pain. 2016;32(2):179-185. 9. Carr AC et al. J Transl Med. 2017;15(1):77. 10. Dionne CE et al. Pain. 2016; 157(11):2527-2535. 11. Chin KY et al. Curr Drug Targets. 2018;19(5):439-450. 12. Ratajczak AE et al. Nutrients. 2020;12(8):2263. 13. Dixit S et al. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2015;6(4):570-581. 14. Monacelli F et al. Nutrients. 2017;9(7):670. 15. Johnston CS et al. J of Nutr. 2007;137(7):1757–1762. 16. Johnston CS et al. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2006;3(35):1743-7075. 17. Moores J. Br J Community Nurs. 2013;Suppl:S6-S11. 18. Carr AC et al. Nutrients. 2017;9:1211. 19. Shaw G et al. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(1):136-143. 20. Ratajczak AE et al. Nutrients. 2020;12(8):2263. 21. Ashor AW et al. Nutr Res. 2019;61:1-12. 22. Moser MA et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(8):1328. 23. Wu JR et al. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2019;34(1):29-35. 24. Akolkar G et al. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2017;313(4):H795-H809. 25. Cook JD et al. Amer J Clin Nutr. 2001;73(1):93-98. 26. Saunders AV et al. Med J Aust. 2013;199(S4):S11-S16. 27. Amr M et al. Nutr J. 2013;12:31. 28. Consoli DC et al. J of neurochem. 2021;157(3):656-665. 29. Bajpai A et al. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(12):CC04-CC7. 30. Koizumi M et al. Nutr Res. 2016;36(12):1379-1391. 31. Whyand T et al. Respir Res. 2018;19(1):79. 32. Azuma A et al. Tairyoku Kagaku Japanese J of Phys Fit and Sports Med. 2019;68(2):153-157. By Melissa Blake, ND

Our bodies have an amazing natural ability of keeping to a daily schedule via an internal 24-hour master clock.1 This clock contributes to the patterns, also known as circadian rhythms, of many biological activities including sleep-wake cycles, eating patterns, and hormone function.1 Finding ways to support and balance this clock, along with the many systems it regulates, may offer a novel way to optimize health. One way to optimize is through diet timing. The circadian diet as a way of eating takes into account not only what we eat, but when.2 It is an approach to eating that synchronizes food intake around our biological clocks, emphasizing eating in sync with the body’s natural tendencies and instincts. This means eating during daylight hours or hours when we are naturally more active. Eating in this way can help support circadian rhythms and contribute to overall health and wellness.2 As diets and terms including intermittent fasting, circadian diet, and time-restricted eating gain popularity, the question may arise as to whether the principle on which this “circadian approach” applies to other aspects of nutrition, including supplementation. 5 common supplements Although there’s still much to learn about optimal timing for both food and supplements, current evidence suggests it may play a role.3 Here are a few general guidelines for five common supplements to help you add the extra layer of timing and optimize your plan: B complex B vitamins are often recommended to support healthy energy and mood.4 There is some evidence that taking B vitamins before bed can have a negative effect on sleep quality.5 Consider taking any B vitamins, including a B complex, earlier in the day with food. Fish oil The most common complaints I hear about fish oil are burping or nausea. Taking fish oil supplements with food, divided into two doses, may help reduce these harmless yet annoying side effects. Magnesium Magnesium is an essential micronutrient that plays a role in hundreds of reactions in the body.6 Due to the overall benefits of magnesium supplementation, consistency is more important than any timing in this case. Known for muscle relaxation and improved sleep, taking magnesium before bed may enhance those benefits in some people.7 Others may notice digestive issues and may choose to take with food. Probiotics Any recommendation related to probiotic supplementation should be based on the specific strain; however, much of this detailed evidence does not yet exist. Meal timing has more or less of an impact on probiotics depending on the strain, the dose, delivery method, etc.8 The consensus, however, is to take probiotics 30 minutes before or during a meal versus after eating.9 Another guideline is to space probiotics away from antibiotic medications by two hours to reduce interaction. Vitamin D Along with vitamins A, E, and K, vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin that is better absorbed when taken with a fat-containing meal (ex. fatty fish, avocado, olive oil, cheese, eggs).10 Although we do not have substantial evidence to support specific timing, it may make sense to take vitamin D supplements in the morning with breakfast to mimic the timing of exposure to natural sunlight. Summary As we continue to learn about specific supplements and optimal timing, consider that the best timing is the one you can stick with. You cannot benefit from a supplement you do not take. The most important thing is to take your supplements at a time that is convenient for you so you can be consistent. Work with a knowledgeable healthcare provider to determine the optimal plan for you that includes quality, quantity, and timing. References:

By Michael Stanclift, ND

Since the 1950s we’ve associated HDL cholesterol with being a positive for our health, and to a large extent, that’s true.1-6 However, more recent studies show us that elevated HDL cholesterol can actually be cause for concern.7,8 So what do we think is going on here? Well, first we have to look at what we’re actually measuring when we look at HDL and why we have assumed that was protective for our cardiovascular systems. For years I taught patients that they can remember the “H” in HDL means that’s the “healthy” cholesterol. While this is mostly a good rule of thumb, the HDL letters actually stand for high-density lipoproteins. High-density lipoproteins are like tiny little garbage trucks that take excess cholesterol out of our system so we can get rid of what we don’t need. And when we measure HDL cholesterol, we’re basically looking at how much “garbage” (cholesterol) is inside those little trucks. It would make sense that the more garbage we find, the more we would assume the trucks are picking up. Unfortunately, this is making a lot of assumptions based on just one finding. We’re assuming that we have enough garbage trucks, that everything on them is working, and that they’ll be dumping that garbage as soon as they get to the landfill (our livers). As you might suspect, those aren’t always the case. Sometimes our HDL particles contain a lot of cholesterol because there are just not that many little garbage trucks to handle all the cholesterol that needs to be transferred.9 Our HDL garbage trucks may also be loaded with cholesterol because they just aren’t unloading it well, which is akin to them driving around full and not picking up more garbage—not useful.10 So what we really want to know when we look at HDL and use that to predict cardiovascular health, is how much healthy HDL function does the patient have? This has been a tricky measure to pin down, but researchers and laboratories are looking to create tests that will give us a clear indication of healthy HDL function and bring that to us as patients. There are a few advanced tests available that can help give indications of our HDL function, but they still need more refinement.9 You’re probably thinking, “Are there ideal HDL levels? When should I seek more investigation?” We do have some indications of ideal levels that suggest our HDL is likely functioning well. One study found the following ideal HDL ranges:9

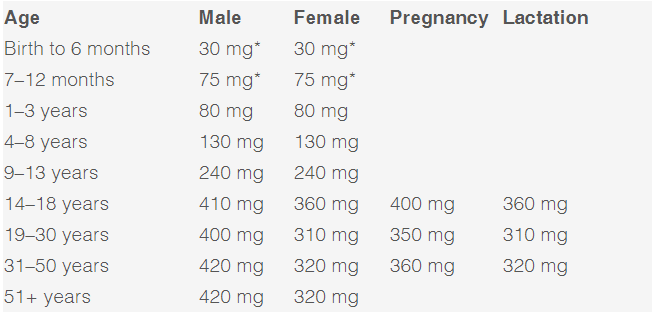

If your HDL levels fall within these ranges, it’s likely functioning as it should, protecting your cardiovascular system and cleaning up other various things your body no longer needs.9 These ranges show us that there is likely an upper limit to what is healthy and ideal and that we might need to rethink the “more is always better” axiom we’ve followed for decades. References: 1. Barr DP et al. Am J Med. 1951;11(4):480-493. 2. Gordon T et al. Am J Med. 1977;62(5):707-714. 3. Castelli WP et al. JAMA. 1986;256(20):2835-2838. 4. Cullen P et al. Circulation. 1997;96(7):2128-2136. 5. Sharrett AR et al. Circulation. 2001;104(10):1108-1113. 6. Di Angelantonio E et al. JAMA. 2009;302(18):1993-2000 7. Madsen CM et al. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2478-2486 8. Hamer M et al. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38(3):669-672. 9. Khera AV et al. Circulation. 2017;135(25):2494-2504. 10. Hancock-Cerutti W et al. Molecules. 2021;26(22):6862. by Bianca Garilli, ND Magnesium is the 4th most abundant mineral in the human body following calcium, sodium, and potassium. Intracellularly, magnesium is the 2nd most abundant cation behind only potassium.1 The number of essential roles magnesium plays in the body is extraordinary, with over 300 enzymes requiring magnesium as a co-factor for proper functioning.1 This essential element is involved in numerous critical physiological processes such as energy production (ATP metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation, and glycolysis), protein synthesis, muscle contraction, nerve function, blood glucose control, hormone receptor binding, blood pressure regulation, trans membrane ion flux, gating of calcium channels, cardiac excitability, and synthesis of nucleic acids (RNA and DNA).1 Unfortunately, magnesium is one of the most prevalent nutrient gaps in the US. The 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee noted a substandard intake of magnesium as compared to the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR), which is the Dietary Reference Intake (DRI) used to assess population sufficiency vs. insufficiency for nutrients.2-3 A 2016 publication in Advanced Nutrition concluded, “Approximately 50% of Americans consume less than the EAR for magnesium, and some age groups consume substantially less”.4 This is especially concerning when one considers the critical implications of long-term, frequently unrecognized magnesium deficiencies. Deficiencies in magnesium can present with overt clinical manifestations such as nausea, vomiting, lethargy, weakness, personality changes, tetany and tremor, seizures, arrhythmia, and muscle fasciculations.5 In other cases, sub clinical deficiencies may be more difficult to recognize yet have equally serious effects if left untreated. Health concerns and disease processes resulting from an underlying, subclinical magnesium deficiency may contribute to low bone mineral density and cardio-metabolic implications such as metabolic syndrome, hypertension, arrhythmia, arterial calcification, atherosclerosis, heart failure, and increased risk for thrombosis.6 A sub clinical magnesium deficiency can also disrupt sleep and cause muscle cramping, two common symptoms often glossed over but which can be signs of a bigger problem if left untreated. The impact of magnesium on these two clinical manifestations will be explored further: Magnesium and sleep A double-blind randomized clinical trial composed of 43 elderly participants between 60-75 years of age with diagnosed insomnia was conducted.7 The experimental group was given 500 mg/day of elemental magnesium for 8 weeks (250 mg elemental magnesium from 414 mg of Mg oxide, twice daily), while the control group received a placebo for the same length of time.7 A statistically significant increase was seen in sleep time, sleep efficiency, and concentration of serum renin and melatonin, as well as a significant decrease in insomnia severity index (ISI) score, sleep onset latency, and serum cortisol level.7 For many individuals, sleep is disrupted by restless leg syndrome (RLS) or periodic limb movements (PLMS).8 A study supplementing 12.4mmol of oral magnesium in the evenings for 4-6 weeks found that the overall sleep efficiency improved from 75 to 85%.9 The Mg-supplemented group also experienced a significant reduction in PLMS associated with arousal (7 PLMS/hr vs. 17 PLMS/hr at baseline).9 Magnesium and muscle cramps Muscle cramping is a common occurrence among women during pregnancy, in athletes, and in the elderly, for which magnesium is often recommended.10 There are only a few studies, however, that have reviewed the efficacy of magnesium for muscle cramping.10 In a Cochrane review, 7 trials (5 parallel, 2 cross-over design) were included, with 3 of these trials studying pregnancy-associated leg cramps in 202 females and 4 trials looking at idiopathic leg cramps in 322 participants.10 Results from the studies noted no significant improvement of muscle cramping in older adults, while results in pregnancy were mixed leading the authors to recommend further studies in this population.10 The authors of a review article in Scientifica note that the mixed findings may be explained by the potential that, “deficiencies of other elemental nutrients including calcium and potassium have also been implicated in muscle cramps and spasms. It may be that magnesium is potentially helpful in situations of magnesium deficiency but is not of use if the problem is related to deficiency of another nutrient.”1 Magnesium: Daily needs and sources Magnesium is an essential macro-mineral required by the human body. The prevalence of deficiency from serum measurements ranges from 12.5-20% of the population.11 Due to the necessity of this cation for over 300 reactions in the human body and the high risk of deficiency, magnesium levels should be routinely monitored either through blood testing and/or a diet diary review. If found to be low, magnesium stores can be replaced through increasing daily intake of the mineral through nutrition as well as routine supplementation. Foods groups high in magnesium content include green leafy vegetables, legumes, nuts, seeds, and whole grains.12 Specific foods with high magnesium levels include spinach, Swiss chard, beet greens, turnip greens, pumpkin seeds, summer squash, soybeans, sesame seeds, quinoa, black beans, cashews, sunflower seeds, brown rice and pinto beans.12 The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for magnesium varies by age, sex, and whether pregnant or lactating:13 *RDA not able to be determined; Adequate Intake (AI) reported

Supplementation with high-quality magnesium is another, targeted way to reach optimal levels and fill dietary gaps. Supplementation dosing and form can be personalized and taken orally via capsules, tablets, liquid, and even powder. Some of the different forms available in the market include Mg oxide, gluconate, chloride, citrate, sulfate, glycinate, and L-threonate. REFERENCES

Bianca Garilli, ND Dr. Garilli is a former US Marine turned Naturopathic Doctor (ND). She works in private practice in Northern California as well as running a consulting company working with leaders in the natural and functional medicine world such as the Institute for Functional Medicine and Metagenics. She is passionate about optimizing health and wellness in individuals, families, companies and communities- one lifestyle change at a time. Dr. Garilli has been on staff at the University of California Irvine, Susan Samueli Center for Integrative Medicine and is faculty at Hawthorn University. She is the creator of the Veterans for Health Initiative and is the current President of the Children’s Heart Foundation, CA Chapter. by Bianca Garilli, ND

Introduction You’re sitting in a relaxing chair at the bookstore with no acute stress or problems, when out of the blue your heart begins to race, flutter, and skip beats. This is not the first time this has happened and you wonder if you might be experiencing a medical emergency. Should you be concerned and call 911, or simply ignore the strange fluttering feelings and continue reading? The answer, as is often the case in medicine: “It depends”. Most likely, though, you are experiencing a common occurrence known as a heart palpitation.1 Heart palpitations can be felt not just in the chest, but often in the throat and neck as well. They may occur during times of activity or while at rest. When experienced for the first time, the flipping and fluttering feeling can be uncomfortable and frightening. However, not all episodes of heart palpitations are dangerous; therefore differentiating those requiring medical intervention from harmless episodes is important.2 What causes heart palpitations? Heart palpitations can have a myriad of causes. Some individuals will experience heart palpitations due to an underlying medical condition such as a hyperthyroidism or other thyroid disorders, blood sugar dysregulation, anemia, or from a drop in blood pressure.2 Heart palpitations may also show up alongside fever or dehydration and some women will even experience hormonally-driven heart palpitations during menstrual cycles, pregnancy, or menopause.3 In certain cases heart palpitations may, in fact, be a sign of a more emergent or progressive chronic condition as in the case of arrhythmias, a heart attack, heart failure, heart valve disease, or cardiomyopathy.2 Heart palpitations accompanied by fainting, dizziness, shortness of breath, or chest pain should be evaluated right away.3 Many times, however, heart palpitations are not indicative of a chronic illness or acute medical situation, but instead may be provoked by our emotional state such as acute stress, fear, anger, or anxiety.3 Other times, daily activities or habits like consuming too much caffeine or alcohol or using nicotine, energy drinks, or illicit drugs can trigger palpitations.3 Other culprits of palpitations include strenuous exercise, electrolyte imbalance, fatigue, and certain medications and supplements. For example, certain medications may cause heart palpitations as a side effect, including: inhaled corticosteroids and albuterol used for asthma; antibiotics such as azithromycin; over-the-counter decongestants containing pseudoephedrine or phenylephrine typically used for colds and coughs; and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) prescribed for depression.3-4 Some supplements such as yohimbe and ephedra (which was banned in the US by the FDA in 2004) may also lead to heart palpitations.5 Hawthorn, an herb which has shown benefits in mild-to-moderate heart failure and sometimes used for managing blood pressure, has been shown to occasionally cause heart palpitations in some people depending on the dose and the individual.4,6 What to do about your heart palpitations? In order to determine the seriousness of your heart palpitations, it’s important to discuss your specific situation with your healthcare provider (HCP), who may decide to order follow-up tests such as blood work, EKG, echocardiogram, or a Holter monitor.3 Steps for reducing or eliminating heart palpitations will depend on whether the underlying cause is a specific medical condition or something more immediately modifiable. Removing or reducing intake of any palpitation-triggering substance is an obvious step in treating this issue. Are there natural approaches to reduce palpitations? Lifestyle modifications can help address palpitations caused by environmental inputs such as stress or emotional situations, nutrition, or exercise. A variety of mind/body techniques can help put a dent in the stressors of life; some examples include tai chi, qi gong, yoga, meditation, breathing, prayer, and biofeedback. Balancing electrolytes through healthful nutrition, hydration, and personalized supplementation is also often helpful. Research indicates that supplementing with CoQ10 or magnesium may provide palpitation relief in some individuals.7-8 One study investigating the effects of CoQ10 on heart failure found that 50 mg/day for 4 weeks led to a reduction in heart palpitations in participants.7 Another study looked at magnesium’s potential role in reducing symptoms associated with mitral valve prolapse in patients with low serum magnesium. Heart palpitations, along with anxiety, weakness, chest pain, and dyspnea are often seen with mitral valve prolapse. After 5 weeks of daily magnesium supplementation (600 mg/day magnesium carbonate supplement given TID the 1st week and BID in weeks 2-5), participants reported a significant reduction in all mitral valve-associated symptoms, including heart palpitations.8 In some cases, heart palpitations may be triggered by certain foods, in particular foods with monosodium glutamate (MSG), nitrates, or too much sodium. In these cases, considering an elimination diet or keeping a food journal may help determine which foods are exacerbating the condition.3 In many situations, heart palpitations are not serious and will go away on their own. Be sure to check with your HCP to discuss your individual experiences and concerns you may have. Citations

Dr. Garilli is a former US Marine turned Naturopathic Doctor (ND). She works in private practice in Northern California as well as running a consulting company working with leaders in the natural and functional medicine world such as the Institute for Functional Medicine and Metagenics. She is passionate about optimizing health and wellness in individuals, families, companies and communities- one lifestyle change at a time. Dr. Garilli has been on staff at the University of California Irvine, Susan Samueli Center for Integrative Medicine and is faculty at Hawthorn University. She is the creator of the Veterans for Health Initiative and is the current President of the Children’s Heart Foundation, CA Chapter. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

|

Join Our Community

|

|

Amipro Disclaimer:

Certain persons, considered experts, may disagree with one or more of the foregoing statements, but the same are deemed, nevertheless, to be based on sound and reliable authority. No such statements shall be construed as a claim or representation as to Metagenics products, that they are offered for the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment or prevention of any disease. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed