|

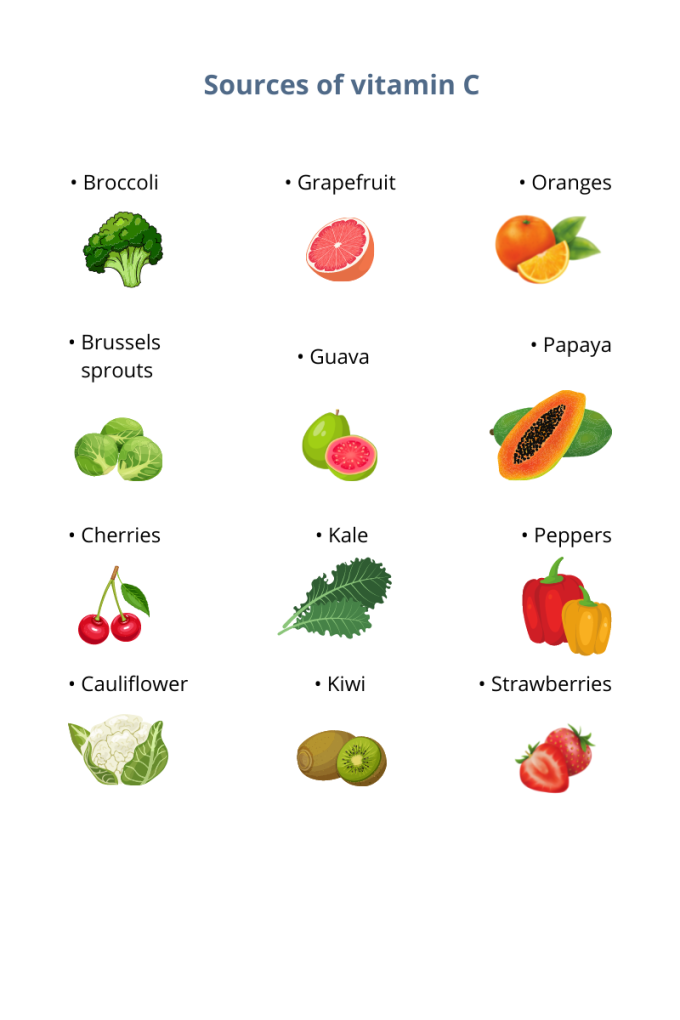

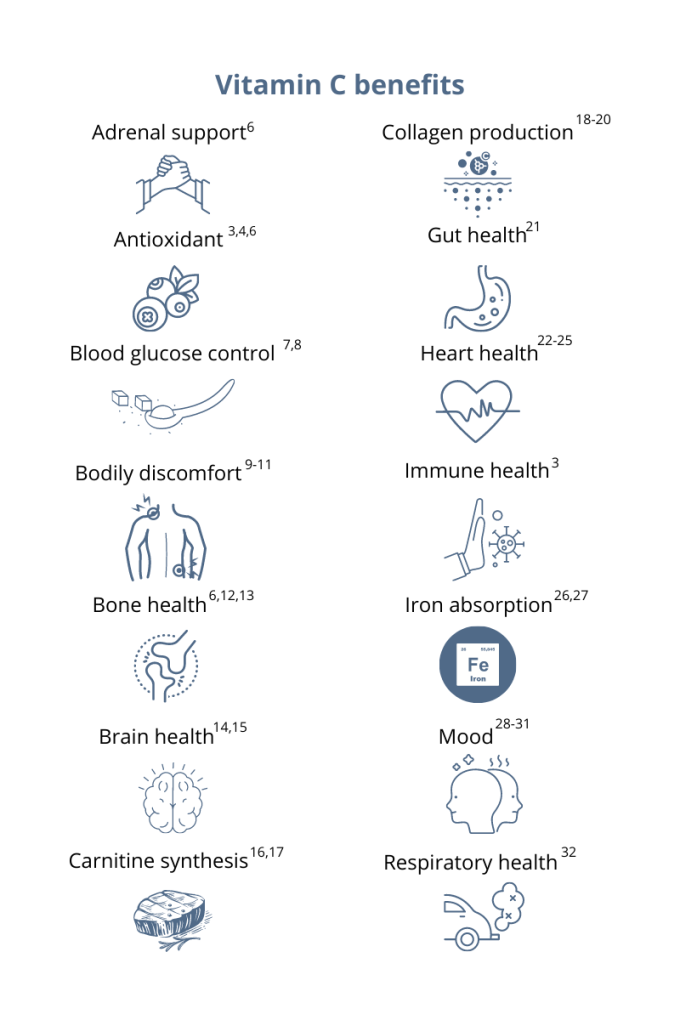

You’ve probably heard that vitamin C supports your immune system. This essential micronutrient seems to be everywhere! And it’s a good thing because, unlike most mammals, humans can’t synthesize vitamin C on their own.1 Also, vitamin C is water-soluble, which means the body quickly loses this essential vitamin through urine, so it’s important to make vitamin C a daily part of your diet.1 Having extremely low levels of vitamin C for prolonged periods can result in scurvy, a historical disease linked to pirates and sailors who faced long journeys at sea without fresh fruits and vegetables. While cases of scurvy in the United States are rare, a recent study reported that 31% of the US population are not meeting the daily recommended intake of vitamin C.1 Greater than 6% of the US population are severely vitamin C deficient, while low levels of vitamin C, associated with weakness and fatigue, were observed in 16% of Americans.2 As a whole, 20% of the US population showed marginally low levels of this essential micronutrient.2 How much vitamin C do I need?The US recommended daily dietary allowance of vitamin C is 75 mg for women and 90 mg for men.3 Experts recommend an estimated 200 mg of vitamin C daily for favorable health benefits.4 Adults can take up to 2,000 mg of vitamin C per day; however, high doses of vitamin C may cause diarrhea, nausea, and stomach cramps.5 Due to the varying health needs of individuals, it’s always a good idea to work with your healthcare practitioner to ensure that you are getting the right amounts of micronutrients in your daily diet. Where can you find this marvelous, multifaceted micronutrient? Ready to add vitamin C to your daily regimen? Talk to your healthcare practitioner about how much would be right for you.

References: 1. Granger M et al. Adv Food Nutr Res. 2018;83:281-310. 2. Schleicher RL et al. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(5):1252-1263. 3. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminC-HealthProfessional/. Accessed August 3, 2021. 4. Frei B et al. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2021;52(9):815-829. 5. Hathcock JN et al. AM J Clin Nutr. 2005;81(4)736-745. 6. Ashor AW et al. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2017;71(12):1371-1380. 7. Mason SA et al. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;93:227-238. 8. Chen S et al. Clin J Pain. 2016;32(2):179-185. 9. Carr AC et al. J Transl Med. 2017;15(1):77. 10. Dionne CE et al. Pain. 2016; 157(11):2527-2535. 11. Chin KY et al. Curr Drug Targets. 2018;19(5):439-450. 12. Ratajczak AE et al. Nutrients. 2020;12(8):2263. 13. Dixit S et al. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2015;6(4):570-581. 14. Monacelli F et al. Nutrients. 2017;9(7):670. 15. Johnston CS et al. J of Nutr. 2007;137(7):1757–1762. 16. Johnston CS et al. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2006;3(35):1743-7075. 17. Moores J. Br J Community Nurs. 2013;Suppl:S6-S11. 18. Carr AC et al. Nutrients. 2017;9:1211. 19. Shaw G et al. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(1):136-143. 20. Ratajczak AE et al. Nutrients. 2020;12(8):2263. 21. Ashor AW et al. Nutr Res. 2019;61:1-12. 22. Moser MA et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(8):1328. 23. Wu JR et al. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2019;34(1):29-35. 24. Akolkar G et al. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2017;313(4):H795-H809. 25. Cook JD et al. Amer J Clin Nutr. 2001;73(1):93-98. 26. Saunders AV et al. Med J Aust. 2013;199(S4):S11-S16. 27. Amr M et al. Nutr J. 2013;12:31. 28. Consoli DC et al. J of neurochem. 2021;157(3):656-665. 29. Bajpai A et al. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(12):CC04-CC7. 30. Koizumi M et al. Nutr Res. 2016;36(12):1379-1391. 31. Whyand T et al. Respir Res. 2018;19(1):79. 32. Azuma A et al. Tairyoku Kagaku Japanese J of Phys Fit and Sports Med. 2019;68(2):153-157.

0 Comments

By Michael Stanclift, ND The rich orange color of turmeric is a signature of this powerfully healthy Indian spice. Even if you don’t dig the flavour of it in food, you might take turmeric in one of its many supplement forms for health benefits. Curcuma longa is the Latin name for turmeric and also hints at the name of the most talked about molecule in it, curcumin. Many people use “turmeric” and “curcumin” interchangeably, but surprisingly there isn’t that much curcumin in turmeric—curcumin makes up only about 3% of dried turmeric.1 But when we’re talking about the health benefits of turmeric, we’re usually really referring to its famous derivative, curcumin, which is the most studied component. So why has this orange molecule become the darling of healthy living? Curcumin offers a host of health perks, is safe, and is well-tolerated by nearly every patient I’ve recommended it to. Many of the effects essentially boil down to curcumin’s ability to function as an antioxidant or balance the immune response to cellular injury.2 It can improve markers of oxidative stress and increase circulating antioxidants, such as superoxide dismutase, sometimes referred to as SOD.2 Curcumin can block the activation of NF-κB, which is involved in the immune response and can lead to undesirable effects.2 So how are these effects meaningful? Here are some of the research-backed ways I’ve utilized curcumin with the patients I’ve seen:

Before you get started There are a few things you should know about curcumin before you run out and start taking it. First, curcumin isn’t very well absorbed, so it is often combined with other natural substances to help improve absorption. I have used it in formulations where it is combined with a black pepper extract (piperine), which can increase the availability about 20 times, and a fenugreek extract, which can increase the availability about 45 times.2,6 The second thing to know is that while curcumin has a great safety record, there have been cases of people taking a curcumin supplement experiencing liver injury.7,8,9 There’s some speculation that the effect may have come from another ingredient, not the curcumin, and many of the products involved contained piperine, the black pepper extract.7,9,10 In response to these concerns, I found a 90-day study of healthy volunteers who were investigated for signs of toxicity when the subjects were given highly bioavailable curcumin (with fenugreek extract).11 With this formulation no adverse effects were noted in the study, and liver enzymes remained within the normal range.11 There are two morals to this story: Always look for manufacturers with a solid reputation and transparent quality testing for their products, and seek the guidance of an experienced healthcare provider to ensure you’re taking the proper precautions and monitoring. In healthy individuals, doses between 150-1,500 mg have been studied and appear to be beneficial, well-tolerated, and safe.5 The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) is a bit more conservative and established an acceptable daily intake (ADI) of curcumin at 3 mg/kg/day.9 For readers in the United States, that translates to roughly 1.36 mg/lb/day or a dose equivalent to about 205 mg/day of curcumin per day for a 150-pound person. Turmeric, along with its most active component curcumin, is clinically versatile and offers a wide range of health benefits. These qualities make it an attractive candidate to include in your healthy lifestyle. Ask your healthcare provider if you might benefit from turmeric or curcumin! References:

By Maribeth Evezich, MS, RD

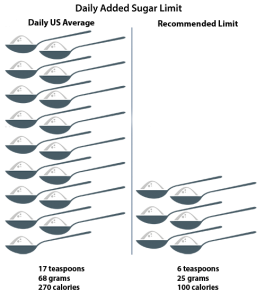

If you’re not monitoring your intake, sugar could be sabotaging your health and weight. Because when it comes to sugar, ignorance is not bliss. Here’s why. Not long ago, added sugars were only a concern due to being “empty calories” promoting obesity and dental cavities. While considered an “unhealthy indulgence,” sugar’s only known risks were to our teeth and waistline and perhaps inadequate nutrition. But then the research started piling up. Today we know better. Over-consumption of added sugar is recognized as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease as well as many other chronic diseases, including diabetes mellitus, liver cirrhosis, and dementia—and is linked to dyslipidemia, hypertension, and insulin resistance.1 So the concern related to added sugar over-consumption has broadened to our whole body with potential health issues from head to toe, literally. In fact, according to UCSF School of Medicine professor Dr. Laura A. Schmidt’s invited commentary in JAMA Internal Medicine, “Too much sugar does not just make us fat; it can also make us sick.”1 Further, excess sugars are associated with premature aging as their by-products build up in connective tissue, promoting stiffness and loss of elasticity.2,3 Think wrinkles. How much is too much? Not surprisingly, major health institutions, such as the Institute of Medicine, World Health Organization (WHO), and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Dietary Guidelines recommend limiting added sugars. Further, the American Heart Association (AHA) has set specific daily limits (see graphic).4 However, while the WHO echoes these guidelines, it encourages further limitation to 5% of daily calories for additional health benefits. That’s 6 teaspoons, 100 calories, 25 grams for a 2,000 calories diet.5 How are we doing? Not well! According to the USDA Dietary Guidelines, on average we’re eating almost 270 calories, or more than 13 percent of calories per day, in added sugars. That’s about 17 teaspoons (approximately 1/3 cup) of added sugars per day, about double the AHA guideline.6 Concerned about your weight? Do the math. That’s 11 teaspoons over the WHO’s more conservative recommendation. So, by simply reducing your added sugars to the lower WHO recommendation, you could be 9 kg lighter a year from now. Where is all this added sugar coming from? Most added sugar comes from processed and prepared foods. Beverages (soft drinks, fruit drinks, sweetened coffee and tea, energy drinks, alcoholic beverages, and flavored waters) are the biggest culprit. For example, with as many as 11 teaspoons (46.2 grams) of added sugar in one 350 ml. soda, a single serving is close to double the recommended limit for women and children. The other major “sugar bombs” are snacks and sweets (grain-based desserts, dairy desserts, puddings, candies, sugars, jams, syrups, and sweet toppings).7 Further, sugar is pervasive in our food supply. You’ll find it lurking in some not-so-obvious places, including savory foods, such as bread and pasta sauce, fruit juices, and bottle sauces, dressings, and condiments, such as ketchup. In fact, you’ll find added sugar in 74% of packaged foods sold in supermarkets, including those marketed as “healthy,” “natural,” “low-fat,” or “gluten-free.”7 They’re everywhere. The only way to keep them at a minimum is to eat whole, minimally processed foods. In the next post in this series, we’ll look at why sugar cravings are so tough to conquer and help you identify hidden sugars in your diet. REFERENCES

"I'm addicted to sugar"

We’ve all heard or thought this before. Considering the American palate for highly processed, overly sweetened foods and the ubiquitous nature of sugar in advertising, we see evidence of a concerning shift. Sugar’s role in the American diet has moved beyond a character actor and into a starring role. Further, as discussed in the previous post, Sugar. How Much Is Too Much?, we consume far more sugar than is recommended for our health. But the question remains—are we addicted? More please: How sugar affects the brain While an ICD-10 code for “sugar addiction,” has yet to be established, an increasing body of research tells us that sugar has addictive effects on the brain.1,2 Like sex and drugs, consuming sugar stimulates the release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter that gives us a sense of euphoria and controls the reward and pleasure centers in the brain. But what may have evolved as a survival mechanism has gone rogue. The caveman sweet tooth From an anthropological perspective, we are hard-wired for sweetness. The pleasing taste of sweet foods was a conditioned reward, one which could increase early man’s survival odds. In times of food scarcity, a preference for more nutritionally dense foods might have provided the energy required to continue the hunt, outrun a predator, or simply avoid starvation. Flash forward a few hundred thousand years, and sugar is exponentially more abundant. Consistent intake of concentrated sugar can lead to changes in the brain’s dopamine receptors. Similar to increased drug or alcohol tolerance, over time, more sugar is needed for the same “high.” Cookies and cocaine So, the more you eat, the more you want. But, as for being “addictive” animal studies have shown sugar consumption to have drug-like effects. These include sugar-related bingeing, craving, tolerance, and withdrawal. In fact, according to a Connecticut College study, Oreo cookies cause more neural activation in the brains of rats than cocaine.3 Taking control For many individuals, the only way to stop over-consuming sugar is to stop the cravings. But the only way to end the cravings is to stop feeding them with sugar. So, in addition to cutting out the obvious forms of sugar—candy, baked goods, etc.—it is important to be aware of the less obvious forms of sugar in your diet. Over the course of a day, small quantities can add up, keep your cravings alive, and thwart your efforts to take control of sugar. So become a sugar sleuth. Here are five tips to get you started. 5 Tips for Identifying Added Sugars

The journey to a healthy relationship with sugar starts with awareness. Watch for the next post in this series, which will feature strategies for taking control of sugar. References

By Maribeth Evezich, MS, RD Sugar. Here’s what we know for sure. As a country we eat too much. It’s everywhere. And it’s possibly addictive. But how do you know if sugar is a problem for you? If in doubt, simply ask yourself who is in control—sugar or you? If you’re not sure if you or sugar is in charge, ask yourself if these situations sound familiar:

If one or more of these statements apply to you, your relationship with sugar may be unhealthy. Most people find that avoiding sugar completely, ideally for several weeks, helps them reclaim control over sugar. Follow these 10 steps to help make it happen.

References:

You eat when you’re hungry. When you’re full, you put down your fork.

It sounds simple, right? Not always. Some of us succumb to cravings even when we’re satiated. In fact, chances are that most of us have experienced cravings at one time or another. A recent study indicated 97% of women and 68% of men report feeling cravings at one time or another.1 But what are cravings? Why do we crave certain foods more than others? And, from a physiological standpoint, how does satiety work? This post will go over the details. What is satiety? Satiety is what we experience after eating a meal or snack. Normal satiety involves not only feeling full after sufficient intake, but also experiencing the need to limit consumption until the next time we get hungry.2 The brain is closely linked to satiety. The central nervous system—and more specifically, the hypothalamus—is responsible for letting us know when we’re ready to stop eating.2 Here are some of the factors that can affect the way we regulate our food intake:2

There are other factors that might occur as well.2 For instance, our physical activity levels and the pleasure we experience from eating can also affect satiety.3 And while most people stop eating when they’re satiated, others may continue to indulge long after the body signals it’s full.2 This is where food cravings come in. What causes cravings? Just as the brain affects satiety, it also plays an important role in food cravings.3,4 Cravings are the products of signals from the brain regions responsible for pleasure, memory, and rewards. These regions include the hippocampus, insula, and caudate. In many cases, the brain regions responsible for memory—those that associate specific foods with pleasure—are especially active when we crave fatty, sugary, or salty foods.4,5 There are a number of other factors that have also been linked to cravings:

Before we move on, it’s worth noting that cravings can be either selective or nonselective in nature. Selective cravings are for specific foods, like a greasy burger or a slice of rich chocolate cake.4 These types of cravings could also be specific for sugar, salt, or fat.4 If you find yourself lingering in the candy aisle, reaching for that pint of ice cream you keep in the freezer, and pouring yourself cup after cup of your favorite sweetened coffee drink, you likely have a selective craving for sugar. Non-selective cravings, conversely, don’t target specific foods. Instead, they represent a desire to eat or drink anything—and they could be the result of real hunger or thirst. If you notice these types of cravings, drink plenty of water and make sure you’re getting enough to eat. By doing so, you may be able to address these non-selective cravings relatively quickly.4,5 What are some strategies for overcoming cravings?While there’s no harm in succumbing to the occasional craving, we should all strive to adopt a nutritious diet. We’ll be healthier and happier, and the brain and body will thank us for eating nutrient-dense foods.1,3-5 With that, here are some tips for overcoming unhealthy food cravings:

So socialize with a friend. Take a hike in nature. Sit down with a good book. Do what you can to relax and find joy in your life and not on your plate.

We can replace our cravings with healthier alternatives.4 For example, instead of reaching for a sugar-laden, fruit-flavored carton of yogurt, opt for the plain alternative and sweeten it yourself—in moderation—with fresh fruit, all-natural honey, or pure maple syrup.

So try not to let yourself get too hungry—and focus on nutritious foods. Eating more protein, healthful fats, colorful produce, and whole grains throughout the day will keep your hunger in check without triggering a potential craving.3-5 While these strategies can help us manage our cravings, they aren’t our only options. Again, it’s essential to drink enough water throughout the day.4 And we can always step away from the fridge the next time a craving hits, and engage in a non-food-related, pleasure-inducing activity instead. We might stretch our muscles, spend time with family, or listen to music. Contacting your healthcare practitioner to discuss cravings and changes to diet may also be a good idea. For more information on nutrition and general wellness topics, please visit the Metagenics blog. References:

Inflammation plays a key role in the immune system.1 This physiological process, the inflammatory response, is the body’s way of protecting itself from infection due to bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other foreign substances.2 Inflammation plays a key role in the body’s natural healing process.1,2

While inflammation is natural—it is necessary in many cases—not all inflammatory responses are created equal.2 Sometimes the body might be inflamed when there are no foreign invaders the immune system needs to fight.2 Far too often, refined sugar is partly responsible.1 So if you have a serious sweet tooth and experience symptoms like redness, joint or muscle stiffness, fatigue, and loss of appetite, you may have fallen victim to the sugar-inflammation connection.1 How does added sugar cause inflammation? Consistently eating high quantities of refined sugar can cause chronic, low-grade inflammation.1 This may lead to serious health issues like cardiovascular challenges, weight gain, or allergies.1,2 Specifically, added sugar promotes the following changes in the body:

While the government recommends that added sugar and solid fats combined account for no more than 5% to 15% of one’s total caloric intake, 13% of US adults’ total calories come from processed sugar.4 All of the above symptoms are linked to chronic, low-grade inflammation. That said, it’s worth noting that added sugar consumption alone is unlikely to cause severe inflammation; often, there are a number of factors at play.1 How can you support a healthier inflammation response? Lifestyle changes can address some of the symptoms mentioned above.1 Examples include: eliminating junk food from your diet, reducing your general stress levels, and so much more.1 Regardless, you will want to take stock of where you are at and make a conscious effort to improve your health.1 Read through the following list to see if there are areas where you can enhance your lifestyle:1,5

Returning to the topic of sugar, there’s no need to give up the sweet stuff entirely. You might consider substituting processed sweets with naturally sweetened alternatives in order to reduce your inflammatory symptoms.1 The next section explains how natural sugars like honey and maple syrup may decrease inflammation. Natural sugars and inflammation Chances are you’re familiar with refined sugar and how it differs from the natural alternatives. Where refined sugar is separated from its source, reconfigured, and then added as a sweetener, natural sugar occurs—you guessed it--naturally in foods.1 This means it is sourced directly from a whole plant source.1 Whole foods like fruit and dairy products feature varying amounts of fructose and lactose—yet they’re also full of fiber, protein, and nutrients, so the body is equipped to process them efficiently.1 Natural sugar is not associated with inflammation.1 It is absorbed more slowly by the body, which helps to minimize blood sugar spikes.1 What does this mean? The verdict is that consuming natural sugar, within moderation, is just fine from a health and wellness standpoint.1 Added sugar, alternatively, should only be eaten rarely and in limited quantities.1 Please contact your doctor if your inflammatory symptoms persist even after eliminating refined sugar from your diet. For more information on nutrition and general wellness topics, please visit the Metagenics blog. References

Submitted by the Metagenics Marketing Team by Ashley Jordan Ferira, PhD, RDN

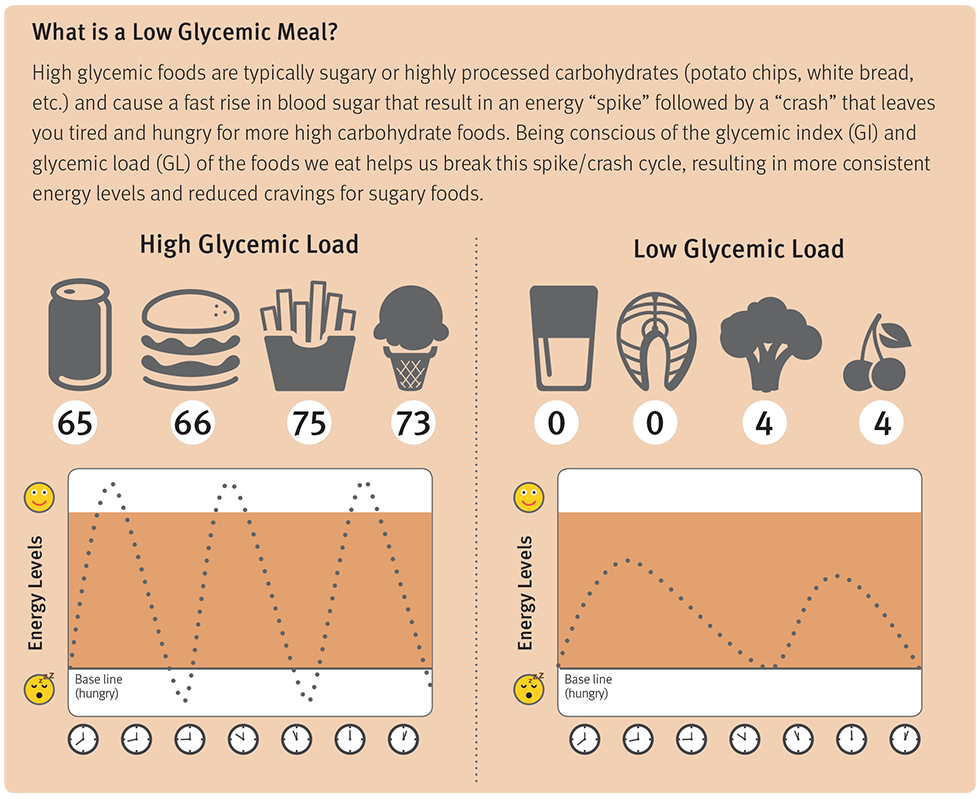

Recent research from three well-known cohorts, The Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), NHS2 and Health Professionals’ Follow-Up Study (HPFS), reveals that higher magnesium intake is associated with lower risk of type 2 diabetes (T2D), particularly in diets with poor carbohydrate quality.1 Green leafy vegetables, unrefined whole grains, and nuts are richest in magnesium, while meats and milk contain a moderate amount.2 Refined foods, like carbohydrates (carb), are poor sources of magnesium. Diets with poor carb quality are characterized by higher glycemic index (GI), higher glycemic load (GL), and lower fiber intake. These poor carbs require a higher insulin demand. The typical American diet is low in vegetables and whole grains, resulting in reduced magnesium intake. The Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) for magnesium is 310-320 mg/day for adult women and 400-420 mg/day for adult men.3 Half of the US population fails to meet their daily magnesium needs, and hypomagnesemia exists in 1/3 of adults.4-5 Magnesium is needed for normal insulin signaling; current research has linked insufficient magnesium intake to prediabetes, insulin resistance and T2D.4 Increased magnesium intake has been inversely associated with T2D risk in observational studies.6 Collaborators from Tufts University, Harvard University, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, sought to investigate the impact of magnesium intake, from both dietary and supplemental sources, on the risk of developing T2D in subjects who had diets with poor carb quality and raised GI, GL, or low fiber intake.1 They followed three large prospective cohorts, NHS, NHS2 and HPFS (totaling over 202,700 participants). Dietary intake was quantified by validated food frequency questionnaires (FFQ) every 4 years, and T2D cases were captured via questionnaires. Over 28 years of follow-up, there were 17,130 cases of T2D. Major study findings included:1

Similar to the US population estimates, 40-50% of study participants had inadequate magnesium intake. A healthful, varied diet and supplemental magnesium (especially in diets that restrict or exclude carbohydrates, dairy or meat) are essential to ensure sufficient daily magnesium intake. Why is this Clinically Relevant?

Citations

Multi-Strain Probiotic Improves Insulin Resistance in Patients with Diabetes | Blog | Metagenics5/11/2019 Targeted probiotic in personalized therapeutic plan for patients with diabetes shows promise by Bianca Garilli, ND and Ashley Jordan Ferira, PhD, RDN Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is no longer a Western world phenomena, but rather a global epidemic, with research revealing an association between higher T2D rates and a country’s wealth or economic growth.1 As a clear example, in a publication titled “Prevalence of type 2 diabetes in the Arab world: impact of GDP and energy consumption”, it was observed that the higher a country’s gross domestic product (GDP), the higher the T2D prevalence.1 T2D rates in these regions include Kingdom of Saudi Arabia- 31.6%, Oman- 29%, Kuwait- 25.4%, Bahrain- 25%, and United Arab Emirates- 25%.1 Recognizing the worldwide impact of T2D, it is critical to identify underlying causes and practical, implementable tools for prevention and treatment. It is well documented that T2D is a chronic, inflammatory condition. Higher levels of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) have been observed in diabetic vs. non-diabetic individuals.2 LPS are Gram-negative bacterial fragments that are considered endotoxins, and can, if left untreated, overgrow in the gastrointestinal tract leading to increased gut permeability.3 A “leaky gut” environment increases the opportunity for these endotoxins to migrate out of the gut and into the circulation, ultimately contributing to systemic inflammation.3 Probiotics have been studied in various models to determine their effects on LPS growth and proliferation and whether targeted probiotic administration aimed at mitigating LPS effects can reduce systemic inflammation, in particular in the T2D population.4-5 The limitations of previous research included short-term duration (≤3 months) and the utilization of mono-strain supplementation.3 To augment the current literature on this topic, a longer study (6 months) was conducted in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled fashion to examine the impact of probiotics on endotoxemia, inflammation, and cardiometabolic disease risk in Arab patients with T2D.3 In this study, 61 Saudi adults (35 females) aged 30-60 years completed the 6-month trial: 30 in the placebo group and 31 in the probiotic group.3 The placebo and probiotic groups were randomly allocated to powder sachets, to be dissolved in a glass of water twice daily, before breakfast and bedtime. The probiotic intervention provided 2.5 billion CFU/g BID and included the following strains: Bifidobacterium bifidum W23, Bifidobacterium lactis W52, Lactobacillus acidophilus W37, Lactobacillus brevis W63, Lactobacillus casei W56, Lactobacillus salivarius W24, Lactococcus lactis W19, and L. lactis W58.3 No additional therapeutics such as exercise or dietary recommendations were included during the course of the study in either group.3 In the probiotic group, significant changes in glycemic indices, lipid profile, inflammatory markers, endotoxin levels, and adipocytokine profile were observed at 6 months vs. baseline:3

The improvements in endotoxin load, inflammation, and cardiometabolic profile over time in the probiotics group are noteworthy, but they were not clinically significant when compared to the placebo group.3 Comparing the probiotic intervention to the placebo group: There was a significant and clinically relevant decrease in HOMA-IR (↓64.2%) in the probiotic group.3 HOMA-IR is correlated with most other cardiometabolic indices measured, so one could posit a potentially broader cardiometabolic benefit from the probiotic intervention, but this and other hypotheses should be explored in a future study with an adequately powered sample size. Why is this Clinically Relevant?

References

“I’m addicted to sugar.” We’ve all heard or thought this before. Considering the American palate for highly processed, overly sweetened foods and the ubiquitous nature of sugar in advertising, we see evidence of a concerning shift. Sugar’s role in the American diet has moved beyond a character actor and into a starring role. Further, as discussed in the previous post, Sugar. How Much Is Too Much?, we consume far more sugar than is recommended for our health. But the question remains—are we addicted? More please: How sugar affects the brain While an ICD-10 code for “sugar addiction,” has yet to be established, an increasing body of research tells us that sugar has addictive effects on the brain.1,2 Like sex and drugs, consuming sugar stimulates the release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter that gives us a sense of euphoria and controls the reward and pleasure centers in the brain. But what may have evolved as a survival mechanism has gone rogue. The caveman sweet tooth From an anthropological perspective, we are hard-wired for sweetness. The pleasing taste of sweet foods was a conditioned reward, one which could increase early man’s survival odds. In times of food scarcity, a preference for more nutritionally dense foods might have provided the energy required to continue the hunt, outrun a predator, or simply avoid starvation. Flash forward a few hundred thousand years, and sugar is exponentially more abundant. Consistent intake of concentrated sugar can lead to changes in the brain’s dopamine receptors. Similar to increased drug or alcohol tolerance, over time, more sugar is needed for the same “high.” Cookies and cocaine So, the more you eat, the more you want. But, as for being “addictive” per se, animal studies have shown sugar consumption to have drug-like effects. These include sugar-related bingeing, craving, tolerance, and withdrawal. In fact, according to a Connecticut College study, Oreo cookies cause more neural activation in the brains of rats than cocaine.3 Taking control For many individuals, the only way to stop over consuming sugar is to stop the cravings. But the only way to end the cravings is to stop feeding them with sugar. So, in addition to cutting out the obvious forms of sugar—candy, baked goods, etc.—it is important to be aware of the less obvious forms of sugar in your diet. Over the course of a day, small quantities can add up, keep your cravings alive, and thwart your efforts to take control of sugar. So become a sugar sleuth. Here are five tips to get you started. 5 Tips for Identifying Added Sugars1. Beware of marketing geared toward dieters

2. Read ingredient labels, especially the first three ingredients

3. Beware of alternate forms and names for sugar

The journey to a healthy relationship with sugar starts with awareness. Watch for the next post in this series, which will feature strategies for taking control of sugar. References

|

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

|

Join Our Community

|

|

Amipro Disclaimer:

Certain persons, considered experts, may disagree with one or more of the foregoing statements, but the same are deemed, nevertheless, to be based on sound and reliable authority. No such statements shall be construed as a claim or representation as to Metagenics products, that they are offered for the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment or prevention of any disease. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed