|

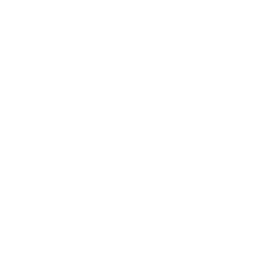

’Tis the season…for the sniffles. Cold and flu viruses are all around us. If you do catch one of them, it’s helpful to understand your symptoms and know when you’re most contagious—so you can avoid sharing the bugs with those around you. Is it just a cold, or is it the flu? Sometimes it can be hard to tell. While both the common cold and the flu are respiratory illnesses, they are caused by different viruses.1 But because symptoms are similar, it may take a little detective work to determine which of these is ailing you. Cold Approximately one billion Americans catch colds each year.2 Symptoms show up gradually and often begin with a sore throat that is later accompanied by congestion (stuffy or runny nose), headaches, and general malaise. With rest and TLC, a cold may ease up within a week.3 Flu While the same feelings of stuffiness may occur, the flu is characterized by the sudden onset of fever, aches and chills, dry cough, and extreme fatigue.4 Unlike colds, the flu can give way to secondary bacterial infections, pneumonia, and other risks,1 so it’s important to take time off and get the rest your body needs to recover. Both children and elderly people are at an increased risk of catching the flu due to lower immunity.1 Stages of illness

Your body goes through several stages when you become ill with a respiratory virus. First, it undergoes a period of incubation (1-2 days) when it is first exposed to the organism. As the virus takes over, onset occurs and symptoms show up—letting you know that you’re unwell. While the flu may hit suddenly, you may detect less obvious signs that you’re coming down with a cold, such as a funny feeling in your throat or feeling tired. As the illness progresses, symptoms may worsen before your body recovers and begins to heal itself. When am I contagious? You are most contagious during the incubation period—before symptoms even start. For both cold and flu, this can persist for several days after you’ve begun to feel sick.4 That’s why allowing yourself adequate downtime early on is so necessary. Cold and flu germs can spread very easily. When you sneeze or cough, germs are expelled through the air and may land on other surfaces or objects, where they can survive for several hours. Touching objects or surfaces with germ-laden fingers carries a big risk for those around you, as they may pick up those germs and become infected.4 To spare friends, family, or coworkers of a similar fate, it’s best to stay home and give your body plenty of recovery time. Staying well No one likes getting sick. Whether there’s a cold or flu floating around your household or office, there are ways to be proactive about your health. If you catch something, do yourself and others a favor by staying home and getting some much-needed rest. If your illness persists or shows excessive symptoms, contact your healthcare practitioner. This information is for educational purposes only. This content is not intended as a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Individuals should always consult with their healthcare professional for advice on medical issues. References:

0 Comments

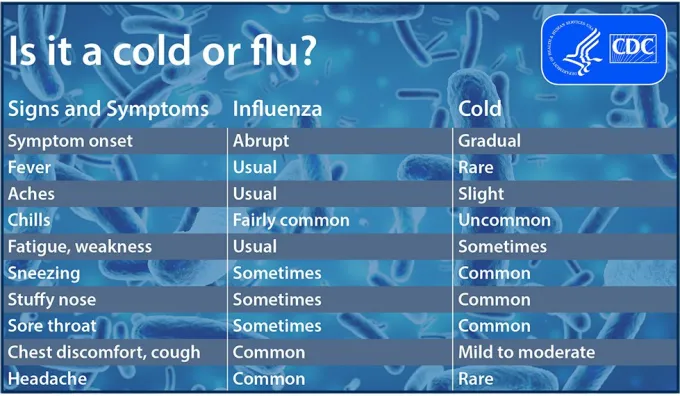

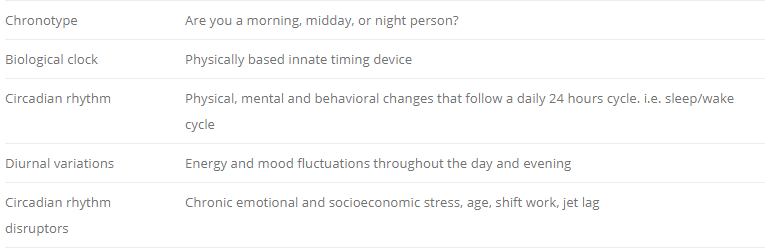

By Daniel Heller, MSc, CSCS, RSCC We’ve all had a bad night’s sleep. And we’ve all felt like we don’t want to do anything physical the day after. We’re human. So do you skip working out that day? The answer is simple. If you have a bad night’s sleep occasionally, show up and modify your workout to adjust to your energy level. If you routinely wake up unrefreshed and tired, see your health care provider. Basic principle: move! Sleeping poorly and feeling tired are two common responses to stress and one of the great excuses to not exercise. Ironically, some form of adjusted physical activity may be the antidote to fatigue and sleeplessness. Your biological clock There is an area of biology worth exploring that can influence the relationship between sleep, energy, and physical activity: your biological clock. Your biological clock is your innate timing device. It is composed of specific molecules (proteins) that interact in cells throughout the body. Biological clocks are found in nearly every tissue and organ. Biological clocks produce circadian rhythms--the physical, mental, and behavioral changes that follow a 24-hour cycle. Sleeping at night and being awake during the day are an example of a light-related circadian rhythm. Other circadian bodily functions include feeding, body temperature, and hormone production. Here’s a quick reference for circadian rhythms.1 Your diurnal variations refer to fluctuations in how you feel in response circadian rhythms throughout the day.2 Finally, your chronotype is the time of day you feel most awake. Chronotype, diurnal variation, exercise, and timing Becoming aware of how the time of day affects you can help inform decisions about when best to engage in physical activities and, to some extent, help you understand how natural rhythms affect the ebb and flow of your feelings. How would you describe your chronotype? Are you a morning person, a midday person, or an evening person? Next, think about diurnal variations in your mood and energy throughout the day and evening. What times are you most productive and energized? What times of day or evening are your low points? Now, assuming you typically sleep well, do your diurnal variations in mood and energy align with your chronotype? For example, if you are a morning person, do you feel energy and a readiness to face the day when you wake? Or, when midday arrives, are you just getting your stride? A word to “night owls:” Allow at least an hour between exercise and bedtime since strenuous physical activity wakes you up.4 If you can align your exercise schedule with your chronotype, this could be ideal timing. Unfortunately, daily commitments conspire to make this problematic. Knowing your diurnal variations in mood and energy offers additional opportunities to choose times that encourage motivation to work out. Recognizing we are hard-wired to our biological clock provides greater insight into forces contributing to how we think, feel, and behave. Knowing this can help you personalize and organize your time, especially around exercise. Sleep disruption, fatigue, and exercise Support yourself through physical activity and explore how best to encourage yourself through the barrier of fatigue. Chronic stress, whether emotional, social, or economic, can disrupt the circadian rhythm affecting your sleep/wake cycle. Some disruption is normal, but see your healthcare provider if you suffer from chronic sleep disturbances. It’s okay to modify your workouts to make it a little easier on yourself, maybe take away a little bit of the complexity of a workout. Research shows that a few physical performance indicators might decrease if we are fatigued, but it does not demonstrate that it should not be done.2,5-7 For example our ability to perform an agility task could be decreased if we’re tired because our coordination might be off and our ability to make quick decisions might be a little slow.2 Knowing that these are potential effects of a poor night’s sleep, consider modifying your workout to keep it safe. The table below provides an illustration of recommendations for workout modification. Sleep disruption, fatigue, and exercise Support yourself through physical activity and explore how best to encourage yourself through the barrier of fatigue. Chronic stress, whether emotional, social, or economic, can disrupt the circadian rhythm affecting your sleep/wake cycle. Some disruption is normal, but see your healthcare provider if you suffer from chronic sleep disturbances. It’s okay to modify your workouts to make it a little easier on yourself, maybe take away a little bit of the complexity of a workout. Research shows that a few physical performance indicators might decrease if we are fatigued, but it does not demonstrate that it should not be done.2,5-7 For example our ability to perform an agility task could be decreased if we’re tired because our coordination might be off and our ability to make quick decisions might be a little slow.2 Knowing that these are potential effects of a poor night’s sleep, consider modifying your workout to keep it safe. The table below provides an illustration of recommendations for workout modification. Research demonstrates that performing an aerobic activity could seem more challenging in a tired state, when compared to being well-rested.7 For example, when you’ve had a full night’s sleep, a particular run normally takes you 45 minutes, but when you haven’t had a full night’s sleep, this same run could take you 55 minutes and seem more difficult to complete. That is all right because you showed up regardless and you did it! You demonstrated your commitment to living an active life! It’s not a matter of a good workout once a month; it’s a matter of consistently being committed to living an active, safe lifestyle.

Before starting or making any changes to your exercise plans, please first consult your healthcare practitioner. References 1. NIH: National Institute of General Medical Sciences. Circadian Rhythms. https://www.nigms.nih.gov/education/pages/factsheet_circadianrhythms.aspx. Accessed September 24, 2019. 2. Romdhani M et al. Total sleep deprivation and recovery sleep affect the diurnal variation of agility performance: the gender differences. J Strength Cond Res. 2018. 3. Lack L et al. Chronotype differences in circadian rhythms of temperature, melatonin, and sleepiness as measured in a modified constant routine protocol. Nat Sci Sleep. 2009;1:1-8. 4. Stutz J et al. Effects of evening exercise on sleep in healthy participants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2019;49(2):269-287. 5. Orzeł-Gryglewska J. Consequences of sleep deprivation. International journal of occupational medicine and environmental health 2010;23:95-114. 6. Skein M et al. Intermittent-Sprint Performance and Muscle Glycogen after 30 h of Sleep Deprivation. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2011;43:1301-1311. 7. Temesi J et al. Does central fatigue explain reduced cycling after complete sleep deprivation. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45:2243-2253. By Melissa Blake, ND

Most likely, you can relate to the immediate impact of a sleepless night. Even a little less sleep may contribute to changes in mood, energy, learning, and appetite.1-3 The long-term consequences of sleep disruptions may be even more serious.4 Thankfully, a glass of wine or whiskey on the rocks is a great way to relax and promote sleep. After all, that’s why it’s called a nightcap. Right? Well, it turns out that alcohol may not be the magic sleep aid we pretend it is, and it may do more harm than good. To understand alcohol’s impact, let’s first talk about rhythms. Master biological clock Our bodies have an amazing natural ability of keeping to a daily schedule via an internal 24-hour master clock.5 This clock contributes to the patterns, also known as circadian rhythms, of many biological activities including sleep-wake cycles, eating patterns, and body temperature regulation.5 Many of the things that we associate with a healthy lifestyle may positively impact circadian health. The same goes for the things we know aren’t good for us—including alcohol: Generally they disrupt our circadian rhythms.6 One way alcohol can disrupt our natural sleep-wake rhythm is by suppressing melatonin, our natural sleep hormone. Research suggests moderate alcohol intake can reduce melatonin by 20%.7 Disruptions to this rhythm can impact health in many ways, often first appearing as changes in sleep, mood, and energy, with eventual negative outcomes that can include weight gain, memory issues, digestive complaints, and changes in immune function.8 How did we fall (asleep) for it? Approximately 20% of Americans use alcohol as a sleep aid.9 If alcohol is disruptive to our natural rhythms, how has it charmed some people into thinking it is the perfect bedtime companion? Alcohol causes short-term drowsiness and contributes to a reduction in sleep onset latency, meaning it shortens the amount of time that it takes to fall asleep.10 Although this sounds like a great solution for people who find themselves lying awake for hours, sedation is not at all the same as natural sleep, and the overall negative impact on sleep quality outweighs immediate sleep-inducing benefits.10,11 Sleep scientist Matthew Walker, PhD avoids using the word “sleep” in connection with alcohol altogether and instead suggests alcohol “sedates you out of wakefulness.”11 Alcohol is also a muscle relaxant. Once again, it may sound like a great solution to any tension that could be interfering with sleep onset. The concern is that alcohol causes the muscles around the neck and throat to relax, which contributes to an increase in snoring, interrupted sleep patterns, and lower oxygen saturation.12,13 Although alcohol may help you feel drowsy and relaxed, the effects are short-lived. Alcohol: not enough REM The impact of alcohol on rapid eye movement (REM) sleep may create some noticeable effects.10 Ever wake after a restless night and feel irritable and moody? It may have been that you didn’t get enough REM sleep.10 Natural, restorative sleep follows a predictive pattern. Much of the first half of the sleep cycle is spent in REM sleep, which is necessary for mental restoration, including processing and regulation of emotions and memory formation. Alcohol disrupts REM sleep pattern and shortens the overall amount.10 This shift in sleep pattern can affect the quality of sleep; however, the impact of alcohol, at any dose, also affects overall quantity of sleep.10,14 As alcohol is metabolized and the sedative effect wears off, a lighter sleep occurs during the second half of the sleep cycle and with it, frequent awakenings related to:14

Alcohol: the vicious cycle Using alcohol as a sleep aid can contribute to a vicious cycle of dependency.15 We’re not always conscious of the frequent “micro”-awakenings associated with our beloved nightcap and therefore may not associate poor sleep quality and next-day fatigue with alcohol consumption. We are tricked into thinking alcohol helped instead of harmed and continue to believe a drink or two is the answer. So a habit of evening drinking is sometimes developed, and over time, tolerance for the sedative effects builds so that more alcohol is required for the same sleep-inducing effect.15 Poor sleep quality leaves us feeling drowsy during the day, and we might turn to caffeine to help clear the fog. Caffeine is a stimulant that can interfere with sleep patterns as well…so we reach for our bottle of choice to counteract the stimulating effects and rely on alcohol to “sedate us out of wakefulness.”11,15 A vicious cycle indeed! The good news is that alcohol intake is modifiable. If you are a great sleeper who wakes rested every day, the occasional drink is likely not the end of the world. For those who choose to enjoy the occasional alcoholic beverage, here are a few tips to reduce the impact on sleep:

References:

As women, we’re constantly seeking balance. Balancing our families and careers, time and energy, work and fun can be a struggle. But balancing that delicate microbiome in our guts doesn’t have to be a challenge, thanks to probiotics. Probiotics are “live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host.”1 There are many myths about probiotics, but the health benefits aren’t one of them. If you’re curious why you should consider taking a daily probiotic and how it can benefit you, consider the following six reasons. 1. Probiotics support immune health. It’s a well-known stereotype that women tend to put others first. The downside of this is that we don’t always take the time to take care of ourselves. The gut plays an active role in immune health, with intestinal bacteria helping to regulate immune cell activity.2 Taking a daily probiotic may be helpful for supporting immune function.3 2. Probiotics can provide self-care for “down there.” Yes, that “down there.” The vagina is an ecosystem that requires a delicate balance, just like the gut. Luckily, there are clinically researched probiotic strains that have been shown specifically to impact feminine health.4 Two such probiotic strains are Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1® and Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14®, which work by traveling through the digestive tract to the vagina.5 Research shows that once there, the two probiotic strains work to help maintain a healthy vaginal environment by increasing the number of good bacteria.4,6,7 3. Certain probiotic strains support weight maintenance. Most people know that a healthy weight correlates to a healthy life.8 But did you know that probiotics can help you maintain that healthy weight? One probiotic strain in particular, Bifidobacterium lactis B-420™, has shown in clinical research that it can help weight maintenance by controlling body fat.9 4. Probiotics support gut health. Women aren’t the only ones whose guts benefit from daily probiotics; this one’s for everyone, even kids! Much research has been done on the benefits of probiotics on gut and digestive health, so it’s no wonder it’s a common reason practitioners recommend this first line therapy for patients seeking digestive support. Look for strains like Bifidobacterium lactis Bi-07® and Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM®, both of which have been researched for their relationship to good gut health.10,11 5. Probiotics can help get mild diarrhea under control. Sometimes we just need a little help getting back to regular. Luckily, there have been many studies done on the relationship between probiotics and gastrointestinal comfort.12 Probiotics like Saccharomyces boulardii and the strain Bifidobacterium lactis HN019 have been studied extensively for their gastrointestinal benefits.13,14 6. Probiotics may help support mood & cognition. Our guts and brains communicate through what’s known as the gut-brain axis.15 In other words, just as stress or unhappiness can lead to an upset tummy, an upset microbiome can affect our mood.14 The opposite works as well: Recent studies have shown that probiotics may help support mood as well as cognition, even to the point of lowering stress levels.16,17 Curious which probiotics would be best for your specific needs? Your healthcare practitioner can help to guide you. For more information on nutrition and gut health, please visit the Metagenics blog. References: 1. Hill C et al. Natur Revs Gastro Hepatol. 2014;11(8):506—514. 2. Bermudez-Brito M et al. Ann Nutr Metab. 2012;61(2):160-174. 3. Kang E-J et al. Korean J Fam Med. 2013;34(1):2-10. 4. Reid G et al. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2001;32(1):37-41. 5. Reid G et al. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2006;30(1):49-52. 6. Reid G et al. J Med Food. 2004;7(2):223-228. 7. Reid G et al. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003;35(2):131-134. 8. Loman T et al. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:259. 9. Stenman LK et al. EBioMedicine. 2016;13:190-200. 10. Ringel-Kulka T et al. J Clin Gastroenter. 2011;45:518-525. 11. Leyer GJ et al. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e172-179. 12. Vitetta L et al. Inflammopharmacol. 2014;22(3):135-154. 13. Kelesidis T. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2012;5(2):111–125. 14. Waller PA et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46(9):1057–1064. 15. Carabotti M et al. Ann Gastroenterol. 2015:28(2):203-209. 16. Papalini S et al. Neurobiology of Stress. 2019;10:100141. 17. Akbari E et al. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnagi.2016.00256/full. Accessed February 19, 2021. NCFM® and Bi-07® are registered trademarks licensed by DuPont. Submitted by the Metagenics team |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

|

Join Our Community

|

|

Amipro Disclaimer:

Certain persons, considered experts, may disagree with one or more of the foregoing statements, but the same are deemed, nevertheless, to be based on sound and reliable authority. No such statements shall be construed as a claim or representation as to Metagenics products, that they are offered for the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment or prevention of any disease. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed