|

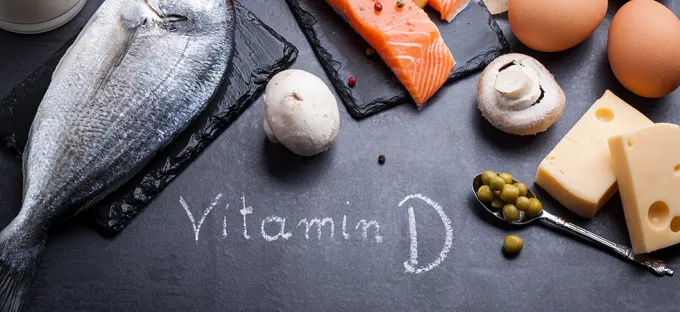

Did you know that getting just 10 minutes of sunshine (ultraviolet B, or UVB) per day helps the body create approximately 10,000 IU of vitamin D?1 This nutrient is necessary for the health of your bones, as well as overall health.2 However, during the months of November through February, and if you live north of Atlanta, there won’t be enough UVB rays to penetrate through the atmosphere and help your skin generate this vital nutrient. So is there something you can do? Sometimes you just have to create your own sunshine. And considering that three-quarters of teens and adults in the United States are deficient in vitamin D,3 as well as 1 billion people worldwide,4 this is where supplemental vitamin D can really help. Natural dietary sources of vitamin D are few (e.g. fatty fish, eggs), and fortified dietary sources such as milk, orange juice and cereal provide minimal amounts of vitamin D. This is why vitamin D is one of the most common nutrient gaps and also one of the easiest to address via supplementation. Why is vitamin D important? Vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin that regulates bone growth and mineralization and plays an important role in ensuring the muscles, heart, lungs, and brain function properly.2 Vitamin D has also been shown to support immune function. Vitamin D is not only an essential vitamin but also acts as a hormone in the body. Vitamin D that you obtain from the sun, food, beverage, or supplements must be first activated by the liver which converts the vitamin D to 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D), also known as calcidiol.2 It is then converted by the kidneys and target tissues in the body to the biologically active form 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)2D), also known as calcitriol.2 Calcitriol is the active, hormone form, which supports a variety of physiological functions, including helping the body regulate levels of calcium and phosphorus, as well as mineralize bone.5 Vitamin D deficiency What does it mean to be deficient in vitamin D? Measuring serum concentrations of 25(OH)D rather than 1,25(OH)2D is a better indicator of vitamin D status in the body due to its longer half life. Certain groups define vitamin D deficiency as 25(OH)D level less than 20 ng/mL (50 nmol/L).6 Vitamin D deficiency can be an issue for many people, including:7

Finding out if you need more vitamin D Measuring your vitamin D levels via a blood test is the only way to definitively know if you’re getting enough of this nutrient. With a 25(OH)D blood test from your healthcare practitioner, you will know your vitamin D levels and whether you need to take a supplement. Optimal levels of vitamin D vary according to different scientific organizations. For example, for adults the Vitamin D Council recommends daily supplementation with 5,000 IU of vitamin D3 when you cannot get enough sun to achieve a status between 40-60 ng/ml; whereas, the Endocrine Society recommends 1500-2000 IU/day.7-8 Higher levels are recommended to address deficiency.8 It is also important to recheck vitamin D levels two months after beginning a supplement regimen, and adjust as needed based on your practitioner’s recommendations. Which D is right for me? It’s important to get the form of vitamin D that is most bioavailable to the body. There are two kinds of vitamin D—D2 and D3. Vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol), is found in plants such as lichens and mushrooms, which are often irradiated by growers to boost nutritional value. Some soy and almond milks are also fortified with vitamin D2. Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) is the natural form of this nutrient that is created by the body with sun exposure, and research has shown that the D3 form increases the total circulating level of 25(OH)D significantly more effectively than D2.9-10 Vitamin D3 is found in small amounts in oily fish such as cod and salmon, egg yolks, as well as fortified cereals and milk, and some commercial mushrooms. Additionally, vitamin D3 has been shown to maintain adequate amounts of serum vitamin D levels during the winter months.11 There are also special sunlamps to help the skin generate vitamin D, but because of the risk for skin damage from ultraviolet rays, many healthcare practitioners don’t recommend using them. Make D your favourite letter for better health Whether you’re lucky enough to get the vitamin D you need from the sun all year around, or taking a vitamin D supplement, you’re wise to ensure you get enough of this vital nutrient. If you’re wondering whether you need more vitamin D, ask your healthcare practitioner. References:

0 Comments

Every BODY and every age have unique nutritional needs. However, with every stage of life, there are common nutritional inadequacies that women are most likely to experience. Learn what supplements are best for YOU! 20s You may find yourself strapped for time and cash during these exciting transitional years, which could result in an unbalanced diet. What supplements should you consider taking?

In your 30s, you may be expanding your family and/or career, so you need all the energy you can get!

Your 40s are filled with possibilities; whether you are starting a new business, climbing the corporate ladder, juggling older kids, or welcoming a new addition, women in their 40s are thriving!

Your 50s and beyond can be a great time to reconnect with yourself and maybe your spouse too. Make sure to support all the amazing years ahead of you with high-quality supplements.

References

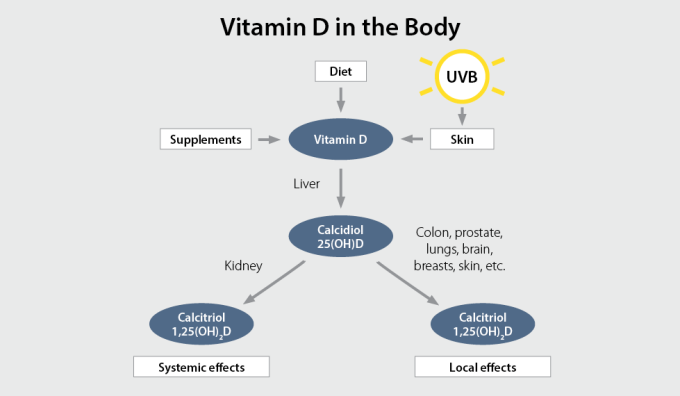

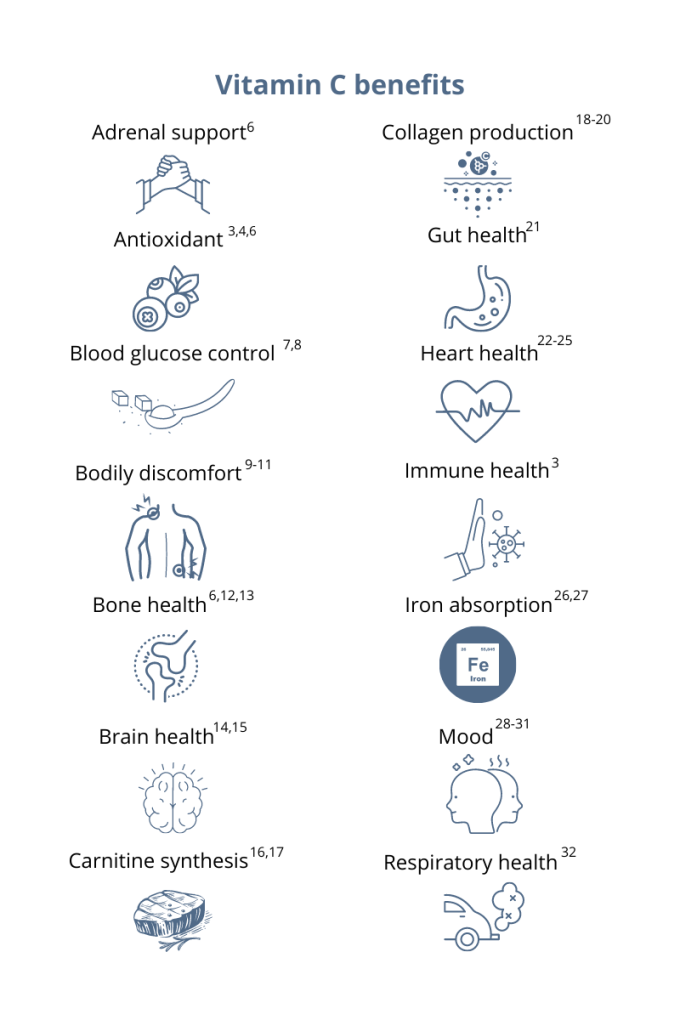

You’ve probably heard that vitamin C supports your immune system. This essential micronutrient seems to be everywhere! And it’s a good thing because, unlike most mammals, humans can’t synthesize vitamin C on their own.1 Also, vitamin C is water-soluble, which means the body quickly loses this essential vitamin through urine, so it’s important to make vitamin C a daily part of your diet.1 Having extremely low levels of vitamin C for prolonged periods can result in scurvy, a historical disease linked to pirates and sailors who faced long journeys at sea without fresh fruits and vegetables. While cases of scurvy in the United States are rare, a recent study reported that 31% of the US population are not meeting the daily recommended intake of vitamin C.1 Greater than 6% of the US population are severely vitamin C deficient, while low levels of vitamin C, associated with weakness and fatigue, were observed in 16% of Americans.2 As a whole, 20% of the US population showed marginally low levels of this essential micronutrient.2 How much vitamin C do I need?The US recommended daily dietary allowance of vitamin C is 75 mg for women and 90 mg for men.3 Experts recommend an estimated 200 mg of vitamin C daily for favorable health benefits.4 Adults can take up to 2,000 mg of vitamin C per day; however, high doses of vitamin C may cause diarrhea, nausea, and stomach cramps.5 Due to the varying health needs of individuals, it’s always a good idea to work with your healthcare practitioner to ensure that you are getting the right amounts of micronutrients in your daily diet. Where can you find this marvelous, multifaceted micronutrient? Ready to add vitamin C to your daily regimen? Talk to your healthcare practitioner about how much would be right for you.

References: 1. Granger M et al. Adv Food Nutr Res. 2018;83:281-310. 2. Schleicher RL et al. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(5):1252-1263. 3. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminC-HealthProfessional/. Accessed August 3, 2021. 4. Frei B et al. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2021;52(9):815-829. 5. Hathcock JN et al. AM J Clin Nutr. 2005;81(4)736-745. 6. Ashor AW et al. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2017;71(12):1371-1380. 7. Mason SA et al. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;93:227-238. 8. Chen S et al. Clin J Pain. 2016;32(2):179-185. 9. Carr AC et al. J Transl Med. 2017;15(1):77. 10. Dionne CE et al. Pain. 2016; 157(11):2527-2535. 11. Chin KY et al. Curr Drug Targets. 2018;19(5):439-450. 12. Ratajczak AE et al. Nutrients. 2020;12(8):2263. 13. Dixit S et al. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2015;6(4):570-581. 14. Monacelli F et al. Nutrients. 2017;9(7):670. 15. Johnston CS et al. J of Nutr. 2007;137(7):1757–1762. 16. Johnston CS et al. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2006;3(35):1743-7075. 17. Moores J. Br J Community Nurs. 2013;Suppl:S6-S11. 18. Carr AC et al. Nutrients. 2017;9:1211. 19. Shaw G et al. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(1):136-143. 20. Ratajczak AE et al. Nutrients. 2020;12(8):2263. 21. Ashor AW et al. Nutr Res. 2019;61:1-12. 22. Moser MA et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(8):1328. 23. Wu JR et al. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2019;34(1):29-35. 24. Akolkar G et al. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2017;313(4):H795-H809. 25. Cook JD et al. Amer J Clin Nutr. 2001;73(1):93-98. 26. Saunders AV et al. Med J Aust. 2013;199(S4):S11-S16. 27. Amr M et al. Nutr J. 2013;12:31. 28. Consoli DC et al. J of neurochem. 2021;157(3):656-665. 29. Bajpai A et al. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(12):CC04-CC7. 30. Koizumi M et al. Nutr Res. 2016;36(12):1379-1391. 31. Whyand T et al. Respir Res. 2018;19(1):79. 32. Azuma A et al. Tairyoku Kagaku Japanese J of Phys Fit and Sports Med. 2019;68(2):153-157. Written by Gauri Yardi

What do a cold, depression, and hayfever have in common? If you said “they’re all health conditions”, or even “they’re all inflammatory health conditions”, you would be right. However, there is something more unusual that connects the three. Give up? All three are influenced by your gut microbiome, the microorganisms that call your digestive tract ‘home’. You may be wondering how these tiny gut inhabitants could have any bearing on your throat, joints, and/or brain. In this article, we will find out how your gut influences these seemingly unrelated areas, as well as how to prevent your gut from making you sick, sad or inflamed. Cold-Busting Colleagues: Your Gut and Immune System Work Hand-in-Hand Your immune system’s main job is to defend you from pathogens (disease-causing microorganisms). Since pathogens are typically inhaled or swallowed, it makes sense for the immune system to concentrate on your respiratory and digestive tracts. In fact, 70% of the immune system is housed in your gut.1 It lies beneath the lining of your intestines, ready to spring into action if a pathogen enters your gut, to try to prevent you getting sick. By contrast, some bacteria have a positive influence on your immune system. A healthy gut microbiome interacts with the intestinal immune system in ways that increase your body’s immune defences. However, a microbiome out of balance, which does not contain high levels of beneficial bacteria, is less likely to help you resist infection, including colds and flu (click here to read more about what might upset your gut microbiome). Fortunately, certain strains (types) of probiotic bacteria improve the bacterial balance in your gut, with beneficial flow-on effects for your immune system. Lactobacillus rhamnosus (LGG®),2 Lactobacillus paracasei (8700:2) and Lactobacillus plantarum (HEAL 9)3 all stimulate the immune system and improve resistance to infection. In fact, the combination of 8700:2 and HEAL 9 has been shown to reduce the severity and duration of common cold symptoms.4 If you struggle with frequent colds and flu, working with a natural healthcare Practitioner to strengthen your gut microbiome may help. A healthy gut microbiome interacts with the intestinal immune system in ways that increase your body’s immune defences. However, a microbiome out of balance, which does not contain high levels of beneficial bacteria, is less likely to help you resist infection, including colds and flu (click here to read more about what might upset your gut microbiome). Jumping at Shadows: The Overactive Immune System Another possible consequence of poor gut bacterial balance is inflammation, a key feature of autoimmune (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis) and allergic disease (e.g. hayfever). In these conditions, the immune system misidentifies harmless substances as threats, and launches an immune response against them. The resulting inflammation creates the symptoms you associate with allergy and autoimmunity, e.g. a blocked nose and watering eyes in hayfever, or joint pain and swelling in rheumatoid arthritis. Fortunately, certain probiotic strains, namely LGG® and Lactobacillus paracasei (LP-33®), can stimulate your immune system to produce anti-inflammatory compounds, reducing inflammation and symptoms. For example, research in hundreds of people has shown that LP-33® significantly improves hayfever symptoms.5,6 Interestingly, LGG®, when taken during pregnancy and breastfeeding, can reduce the incidence of eczema (an inflammatory skin disease) in children, by supporting the healthy development of the gut microbiome and the immune system.7 If your immune system is in overdrive, make an appointment with a natural healthcare Practitioner to help bring it back into line. Gut Feelings: How Bacteria Make or Break Your MoodMore and more research is supporting an unexpected cause of depression: inflammation. Specifically, inflammation throughout the body (known as systemic inflammation), and even inflammation of the brain, may contribute to depression. As you have already learned, the interaction between bad gut bacteria and the immune system can cause inflammation. However, did you know that the inflammatory chemicals released within your gut can also cause an inflammatory response in your brain? If gut inflammation can influence mood, you may be wondering if specific probiotics can improve mood or reduce the symptoms of depression. While this is a hot topic in scientific research, we do not currently know which specific probiotic strains can influence mood. However, a good start in supporting healthy mood is taking steps to reduce inflammation in the body. What we do know is maximising your gut health, e.g. by eating plenty of fibre-rich wholefoods (to provide your gut bacteria with their preferred food), can also increase the numbers of good bacteria, which is the best way to influence your mood via your gut. If your bacterial balance has become disrupted due to a stomach bug, antibiotics, or other causes, strains which support beneficial bacteria, such as LGG®, Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii, and Bifidobacterium animalis ssp lactis (BB-12®) may help improve the composition of your gut microbiome. Great Health is All in the Gut By interacting with your immune system, your gut bacteria influences your ability to resist infection, reduce inflammation, and maintain a healthy mood. If you are wondering whether your gut may be making you sick, sad or inflamed, make an appointment with a natural healthcare Practitioner today. Together, you can assess your bacterial balance, and make a plan to improve your specific symptoms. References1 Gill HS. Probiotics to enhance anti-infective defences in the gastrointestinal tract. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;17(5):755-773. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6918(03)00074-x. 2 Feleszko W, Jaworska J, Rha RD, Steinhausen S, Avagyan A, Jaudszus A, et al. Probiotic-induced suppression of allergic sensitization and airway inflammation is associated with an increase of Tregulatory-dependent mechanisms in a murine model of asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37(4):498-505. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02629.x. 3 Lavasani S, Dzhambazov B, Nouri M, Fåk F, Buske S, Molin G, et al. A novel probiotic mixture exerts a therapeutic effect on experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mediated by IL-10 producing regulatory T cells. PLoS One. 2010; 5(2): e9009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009009. 4 Berggren A, Lazou Ahrén I, Larsson N, Önning G.. Randomised, double-blind and placebo-controlled study using new probiotic lactobacilli for strengthening the body immune defence against viral infections. Eur J Nutr 2011; 50(3):203-210. doi: 10.1007/s00394-010-0127-6. 5 Costa DJ, Marteau P, Amouyal M, Poulsen LK, Hamelmann E, Czaaubiel M, et al. Efficacy and safety of the probiotic Lactobacillus paracasei LP-33 in allergic rhinitis: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial (GA2LEN) study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014 May;68(5):602-7. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.13. 6 Peng G-C, Hsu C-H. The efficacy and safety of heat-killed Lactobacillus paracasei for treatment of perennial allergic rhinitis induced by house-dust mite. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2005 Aug;16(5):433-438. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2005.00284.x. 7 Kalliomäki M, Salminen S, Arvilommi H, Kero P, Koskinen P, Isolauri E. Probiotics in primary prevention of atopic disease: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;357(9262):1076-9. By Melissa Blake, ND

Our bodies have an amazing natural ability of keeping to a daily schedule via an internal 24-hour master clock.1 This clock contributes to the patterns, also known as circadian rhythms, of many biological activities including sleep-wake cycles, eating patterns, and hormone function.1 Finding ways to support and balance this clock, along with the many systems it regulates, may offer a novel way to optimize health. One way to optimize is through diet timing. The circadian diet as a way of eating takes into account not only what we eat, but when.2 It is an approach to eating that synchronizes food intake around our biological clocks, emphasizing eating in sync with the body’s natural tendencies and instincts. This means eating during daylight hours or hours when we are naturally more active. Eating in this way can help support circadian rhythms and contribute to overall health and wellness.2 As diets and terms including intermittent fasting, circadian diet, and time-restricted eating gain popularity, the question may arise as to whether the principle on which this “circadian approach” applies to other aspects of nutrition, including supplementation. 5 common supplements Although there’s still much to learn about optimal timing for both food and supplements, current evidence suggests it may play a role.3 Here are a few general guidelines for five common supplements to help you add the extra layer of timing and optimize your plan: B complex B vitamins are often recommended to support healthy energy and mood.4 There is some evidence that taking B vitamins before bed can have a negative effect on sleep quality.5 Consider taking any B vitamins, including a B complex, earlier in the day with food. Fish oil The most common complaints I hear about fish oil are burping or nausea. Taking fish oil supplements with food, divided into two doses, may help reduce these harmless yet annoying side effects. Magnesium Magnesium is an essential micronutrient that plays a role in hundreds of reactions in the body.6 Due to the overall benefits of magnesium supplementation, consistency is more important than any timing in this case. Known for muscle relaxation and improved sleep, taking magnesium before bed may enhance those benefits in some people.7 Others may notice digestive issues and may choose to take with food. Probiotics Any recommendation related to probiotic supplementation should be based on the specific strain; however, much of this detailed evidence does not yet exist. Meal timing has more or less of an impact on probiotics depending on the strain, the dose, delivery method, etc.8 The consensus, however, is to take probiotics 30 minutes before or during a meal versus after eating.9 Another guideline is to space probiotics away from antibiotic medications by two hours to reduce interaction. Vitamin D Along with vitamins A, E, and K, vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin that is better absorbed when taken with a fat-containing meal (ex. fatty fish, avocado, olive oil, cheese, eggs).10 Although we do not have substantial evidence to support specific timing, it may make sense to take vitamin D supplements in the morning with breakfast to mimic the timing of exposure to natural sunlight. Summary As we continue to learn about specific supplements and optimal timing, consider that the best timing is the one you can stick with. You cannot benefit from a supplement you do not take. The most important thing is to take your supplements at a time that is convenient for you so you can be consistent. Work with a knowledgeable healthcare provider to determine the optimal plan for you that includes quality, quantity, and timing. References:

By Michael Stanclift, ND The rich orange color of turmeric is a signature of this powerfully healthy Indian spice. Even if you don’t dig the flavour of it in food, you might take turmeric in one of its many supplement forms for health benefits. Curcuma longa is the Latin name for turmeric and also hints at the name of the most talked about molecule in it, curcumin. Many people use “turmeric” and “curcumin” interchangeably, but surprisingly there isn’t that much curcumin in turmeric—curcumin makes up only about 3% of dried turmeric.1 But when we’re talking about the health benefits of turmeric, we’re usually really referring to its famous derivative, curcumin, which is the most studied component. So why has this orange molecule become the darling of healthy living? Curcumin offers a host of health perks, is safe, and is well-tolerated by nearly every patient I’ve recommended it to. Many of the effects essentially boil down to curcumin’s ability to function as an antioxidant or balance the immune response to cellular injury.2 It can improve markers of oxidative stress and increase circulating antioxidants, such as superoxide dismutase, sometimes referred to as SOD.2 Curcumin can block the activation of NF-κB, which is involved in the immune response and can lead to undesirable effects.2 So how are these effects meaningful? Here are some of the research-backed ways I’ve utilized curcumin with the patients I’ve seen:

Before you get started There are a few things you should know about curcumin before you run out and start taking it. First, curcumin isn’t very well absorbed, so it is often combined with other natural substances to help improve absorption. I have used it in formulations where it is combined with a black pepper extract (piperine), which can increase the availability about 20 times, and a fenugreek extract, which can increase the availability about 45 times.2,6 The second thing to know is that while curcumin has a great safety record, there have been cases of people taking a curcumin supplement experiencing liver injury.7,8,9 There’s some speculation that the effect may have come from another ingredient, not the curcumin, and many of the products involved contained piperine, the black pepper extract.7,9,10 In response to these concerns, I found a 90-day study of healthy volunteers who were investigated for signs of toxicity when the subjects were given highly bioavailable curcumin (with fenugreek extract).11 With this formulation no adverse effects were noted in the study, and liver enzymes remained within the normal range.11 There are two morals to this story: Always look for manufacturers with a solid reputation and transparent quality testing for their products, and seek the guidance of an experienced healthcare provider to ensure you’re taking the proper precautions and monitoring. In healthy individuals, doses between 150-1,500 mg have been studied and appear to be beneficial, well-tolerated, and safe.5 The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) is a bit more conservative and established an acceptable daily intake (ADI) of curcumin at 3 mg/kg/day.9 For readers in the United States, that translates to roughly 1.36 mg/lb/day or a dose equivalent to about 205 mg/day of curcumin per day for a 150-pound person. Turmeric, along with its most active component curcumin, is clinically versatile and offers a wide range of health benefits. These qualities make it an attractive candidate to include in your healthy lifestyle. Ask your healthcare provider if you might benefit from turmeric or curcumin! References:

By Molly Knudsen, MS, RDN

There’s no doubt that antioxidants are good for health. Antioxidants have been in the public spotlight since the 1990s and have only gained attention over the years, basically reaching celebrity status. And that status has not wavered, especially as their role in immune health becomes increasingly known. Antioxidants and antioxidant-rich foods continue to trend and make headlines, most recently in the forms of matcha/green tea drinks, acai bowls, golden milk, or just good ol’ fashioned fresh fruits and vegetables. Antioxidants are here to stay not only because they’re found in delicious foods, but they also play a vital role in health by protecting the body against oxidative stress.1 What is oxidative stress? Everyone’s heard of oxidative stress, but what exactly does that refer to? Oxidative stress occurs from damage caused by free radicals. Free radicals are unstable molecules that have lost an electron from either normal body processes like metabolism, reactions due to exercise, or from external sources like cigarette smoke, pollutants, or radiation.1 Now electrons don’t like to be alone. They like to be in pairs. So do free radicals suck it up and leave one of their electrons unpaired? Nope. They steal an electron from another healthy molecule, turning that molecule into another free radical and, if excessive, wreak havoc in the body and its defense system. Immune cells are particularly vulnerable to oxidative stress because of the type of fat (polyunsaturated) that they have in their membrane.2 So high amounts of oxidative stress over time can be especially detrimental to immune system. What are antioxidants? Antioxidants are the heroes that can break this cycle. And there’s not just one antioxidant. Antioxidants refer to a whole class of molecules (including certain vitamins, minerals, compounds found in plants, and some compounds formed in the body) that share the same goal of protecting the body and the immune system against oxidative stress.2 But different foods contain different antioxidants, and each antioxidant has its own unique way of supporting that goal. 6 antioxidants for oxidative stress protection + immune health 1. Vitamin C Vitamin C is a powerful antioxidant that also contributes to immunity. It works by readily giving up one of its electrons to free radicals, thereby protecting important molecules like proteins, fats, and carbohydrates from damage.3 Vitamin C is a water-soluble vitamin, which means storage in the body is limited, and consistent intake of this nutrient is vital. Research shows that not getting enough vitamin C can impact immunity by weakening the body’s defense system.3 Vitamin C is found in many fruits and vegetables, including strawberries, bell peppers, citrus, kiwi, and broccoli. The benefits of vitamin C’s antioxidant capabilities are more than just internal. Benefits are also seen when a concentrated source of this antioxidant is applied to the skin. For example, topical vitamin C serums are often recommended by dermatologists and estheticians to help protect the skin from sunlight and address hyperpigmentation.4 2. Epigallocatechin 3-gallate (EGCG) Green tea is easily, and unofficially, considered one of the world’s healthiest foods, and the presence of EGCG is one reason for this drink’s reputation. EGCG is the most abundant, potent, and researched polyphenolic antioxidant found in green tea leaves.5 It has been shown to protect against damage caused by free radicals.5 Drinking green tea is a great way to reap the benefits of EGCG and other nutrients found in tea leaves, or it’s also available as an extract in nutritional supplements. If you choose to drink green tea, it’s important to remember that water preparation matters. Using hot water to steep green tea not only preserves, but it also encourages more antioxidant activity compared to using cold water, as hot water may be better at extracting polyphenols from the leaves.5 3. Glutathione Glutathione is a powerful antioxidant that the body actually makes internally from three amino acids (AKA building blocks of protein): cysteine, glutamate, and glycine.6 Not only does this antioxidant protect the body against oxidative stress, it also supports healthy liver detoxification processes.7 Glutathione levels naturally decrease with age, and lower glutathione levels in the body are associated with poorer health.8 Since it takes all three of those amino acids to form glutathione, ensuring that the body has adequate levels of all three is vital. Cysteine is the difficult one. It’s considered the “rate-limiting” step in this equation, since it’s usually the one in short supply, and glutathione can’t be formed without it.6 Cysteine contains sulfur, so foods like unprocessed meat, garlic, and asparagus are great choices to support cysteine levels. Like cysteine, the compound N-acetylcysteine (found in supplements and often labeled NAC) can also be used to support the body’s glutathione levels.6 4. Curcumin Curcumin is the yellow pigment and considered the active ingredient in the spice turmeric. In the culinary world, turmeric is best known for playing the leading role in curries as well as in golden milk. Studies show that curcumin has been shown to improve markers of oxidative stress, act as a free radical scavenger, and assist with other antioxidant processes in the body.9 Curcumin isn’t very bioavailable, so your body isn’t able to fully capture the benefits when consumed on its own or just as turmeric.9 But adding other spices or herbs like black pepper or fenugreek can significantly increase your body’s ability to utilize curcumin.9 5. Vitamin E Vitamin E is a fat-soluble vitamin, meaning it’s best absorbed with fat. It acts as an antioxidant by stopping the production of free radicals from forming when fat is oxidized, or burned.10 Vitamin E is found in nuts and seeds (almonds, sunflower seeds, and hazelnuts) as well as green leafy vegetables. Vitamin E also plays a role in heart, eye, and cognitive health.10 6. Quercetin Quercetin is one of the most well-studied flavonoids, or plant compounds, typically found in onions, kale, broccoli, apples, and tea. Quercetin acts as a free radical-scavenging antioxidant, helps inhibit oxidative stress, and supports a healthy immune response.11 What’s the bottom line? Antioxidants are a crucial part to any healthful diet. They help protect the body from damage caused by oxidative stress and support immune function. There are many more antioxidants that are beneficial to health than those listed here. The best way to ensure that you’re getting enough antioxidants from the diet and supporting the antioxidants the body makes on its own is to consume a diet high in plants like fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, and legumes. References

By Melissa Blake, ND

When it comes to building a healthy immune system, we often hear about diet and exercise, but unfortunately less often about the importance of sleep. But, when it comes to the immune system, sleep is a crucial component. Researchers around the world continue to discover the numerous benefits of our nightly slumber. Sleep is when the body and the mind have a chance to rest and repair on a cellular level, and without enough of it, or enough quality sleep, one’s health can begin to suffer.1 Disrupted sleep is a major contributor to hormone imbalances, skin issues, weight gain, and even a weakened immune system.1-4 Whether you’re not sleeping well due to stress, your schedule, or another factor, prioritizing sleep is a key component to a healthy immune system.1 The sleep debt cost Most likely everyone can relate to the immediate impact of a sleepless night. Even getting just a little less sleep than one needs or is used to can contribute to confusion, weakness, muscle pain, and changes in appetite.2-4 The long-term consequences of neglecting sleep are even more serious. A regular lack of sleep increases the risk of cardiovascular issues, weight gain, and compromised immune function.4,5 Correlation between sleep & immune health Driven by a circadian rhythm, messengers called cytokines impact the state of the immune system and also contribute to sleep-wake patterns.1 While we are sleeping, cytokines instruct immune cells to work hard at repairing damage, clearing toxins, and defending us against illness.1 This might be one reason why we feel more tired and require more rest when we are sick. It’s during sleep that the immune system is most active and focused on recovery and developing immune memory.1 A good night’s rest is also key for improving the function of immune cells known as T cells, a type of immune cell that fights against pathogens such as viruses.6 A German study found that in people who slept adequately the night before, T cells were better able to attach to their targets, including virus-infected cells, than in the T cells of those who stayed up all night.7 The findings highlight one of many immune-supportive effects of sleep. Conclusion Habits such as a consistent routine, including regular bed and wake times, as well as exposure to natural sunlight within an hour of waking are small, simple changes people can make in order to get a better night’s sleep while improving their body’s circadian health. Even going to bed just 10 minutes earlier can have a profound effect on how you feel, so give it a try starting tonight—your immune system will thank you. This is the first in a three-part series on circadian health. For more information on sleep and other general wellness topics, please visit the Metagenics blog. References:

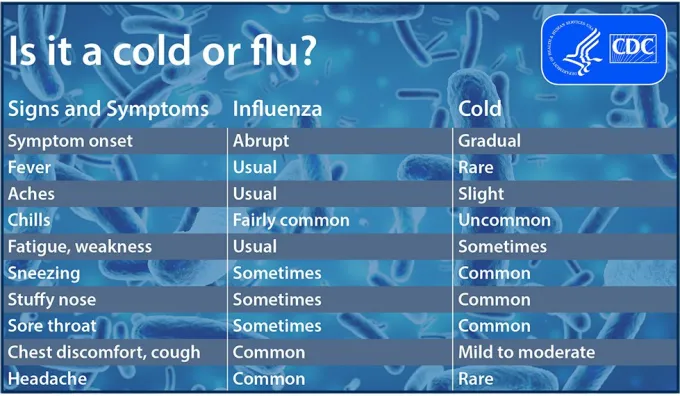

’Tis the season…for the sniffles. Cold and flu viruses are all around us. If you do catch one of them, it’s helpful to understand your symptoms and know when you’re most contagious—so you can avoid sharing the bugs with those around you. Is it just a cold, or is it the flu? Sometimes it can be hard to tell. While both the common cold and the flu are respiratory illnesses, they are caused by different viruses.1 But because symptoms are similar, it may take a little detective work to determine which of these is ailing you. Cold Approximately one billion Americans catch colds each year.2 Symptoms show up gradually and often begin with a sore throat that is later accompanied by congestion (stuffy or runny nose), headaches, and general malaise. With rest and TLC, a cold may ease up within a week.3 Flu While the same feelings of stuffiness may occur, the flu is characterized by the sudden onset of fever, aches and chills, dry cough, and extreme fatigue.4 Unlike colds, the flu can give way to secondary bacterial infections, pneumonia, and other risks,1 so it’s important to take time off and get the rest your body needs to recover. Both children and elderly people are at an increased risk of catching the flu due to lower immunity.1 Stages of illness

Your body goes through several stages when you become ill with a respiratory virus. First, it undergoes a period of incubation (1-2 days) when it is first exposed to the organism. As the virus takes over, onset occurs and symptoms show up—letting you know that you’re unwell. While the flu may hit suddenly, you may detect less obvious signs that you’re coming down with a cold, such as a funny feeling in your throat or feeling tired. As the illness progresses, symptoms may worsen before your body recovers and begins to heal itself. When am I contagious? You are most contagious during the incubation period—before symptoms even start. For both cold and flu, this can persist for several days after you’ve begun to feel sick.4 That’s why allowing yourself adequate downtime early on is so necessary. Cold and flu germs can spread very easily. When you sneeze or cough, germs are expelled through the air and may land on other surfaces or objects, where they can survive for several hours. Touching objects or surfaces with germ-laden fingers carries a big risk for those around you, as they may pick up those germs and become infected.4 To spare friends, family, or coworkers of a similar fate, it’s best to stay home and give your body plenty of recovery time. Staying well No one likes getting sick. Whether there’s a cold or flu floating around your household or office, there are ways to be proactive about your health. If you catch something, do yourself and others a favor by staying home and getting some much-needed rest. If your illness persists or shows excessive symptoms, contact your healthcare practitioner. This information is for educational purposes only. This content is not intended as a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Individuals should always consult with their healthcare professional for advice on medical issues. References:

by Erik Lundquist, MD

Looking for ways to support healthy immune function? Erik Lundquist, MD shared a variety of options to consider as ways to help support immune health. Here are some formula recommendations he gives to his patients: Vitamins:

Keeping clean & healthy Maintaining good hygiene helps keep the immune system healthy. Consider these simple preventative measures that should be followed routinely to ensure good hygiene practices.

References:

|

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

|

Join Our Community

|

|

Amipro Disclaimer:

Certain persons, considered experts, may disagree with one or more of the foregoing statements, but the same are deemed, nevertheless, to be based on sound and reliable authority. No such statements shall be construed as a claim or representation as to Metagenics products, that they are offered for the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment or prevention of any disease. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed