|

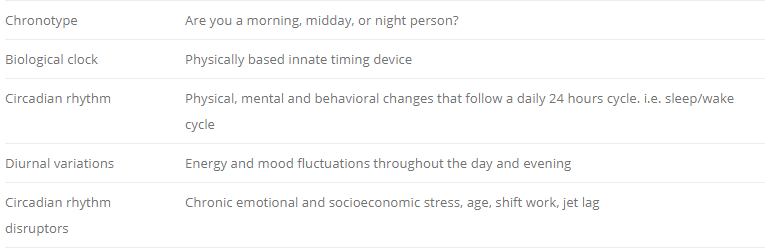

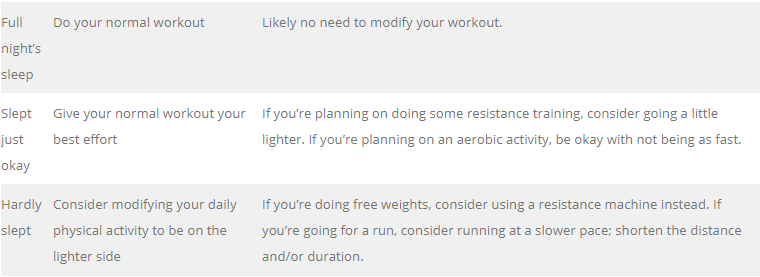

By Daniel Heller, MSc, CSCS, RSCC We’ve all had a bad night’s sleep. And we’ve all felt like we don’t want to do anything physical the day after. We’re human. So do you skip working out that day? The answer is simple. If you have a bad night’s sleep occasionally, show up and modify your workout to adjust to your energy level. If you routinely wake up unrefreshed and tired, see your health care provider. Basic principle: move! Sleeping poorly and feeling tired are two common responses to stress and one of the great excuses to not exercise. Ironically, some form of adjusted physical activity may be the antidote to fatigue and sleeplessness. Your biological clock There is an area of biology worth exploring that can influence the relationship between sleep, energy, and physical activity: your biological clock. Your biological clock is your innate timing device. It is composed of specific molecules (proteins) that interact in cells throughout the body. Biological clocks are found in nearly every tissue and organ. Biological clocks produce circadian rhythms--the physical, mental, and behavioral changes that follow a 24-hour cycle. Sleeping at night and being awake during the day are an example of a light-related circadian rhythm. Other circadian bodily functions include feeding, body temperature, and hormone production. Here’s a quick reference for circadian rhythms.1 Your diurnal variations refer to fluctuations in how you feel in response circadian rhythms throughout the day.2 Finally, your chronotype is the time of day you feel most awake. Chronotype, diurnal variation, exercise, and timing Becoming aware of how the time of day affects you can help inform decisions about when best to engage in physical activities and, to some extent, help you understand how natural rhythms affect the ebb and flow of your feelings. How would you describe your chronotype? Are you a morning person, a midday person, or an evening person? Next, think about diurnal variations in your mood and energy throughout the day and evening. What times are you most productive and energized? What times of day or evening are your low points? Now, assuming you typically sleep well, do your diurnal variations in mood and energy align with your chronotype? For example, if you are a morning person, do you feel energy and a readiness to face the day when you wake? Or, when midday arrives, are you just getting your stride? A word to “night owls:” Allow at least an hour between exercise and bedtime since strenuous physical activity wakes you up.4 If you can align your exercise schedule with your chronotype, this could be ideal timing. Unfortunately, daily commitments conspire to make this problematic. Knowing your diurnal variations in mood and energy offers additional opportunities to choose times that encourage motivation to work out. Recognizing we are hard-wired to our biological clock provides greater insight into forces contributing to how we think, feel, and behave. Knowing this can help you personalize and organize your time, especially around exercise. Sleep disruption, fatigue, and exercise Support yourself through physical activity and explore how best to encourage yourself through the barrier of fatigue. Chronic stress, whether emotional, social, or economic, can disrupt the circadian rhythm affecting your sleep/wake cycle. Some disruption is normal, but see your healthcare provider if you suffer from chronic sleep disturbances. It’s okay to modify your workouts to make it a little easier on yourself, maybe take away a little bit of the complexity of a workout. Research shows that a few physical performance indicators might decrease if we are fatigued, but it does not demonstrate that it should not be done.2,5-7 For example our ability to perform an agility task could be decreased if we’re tired because our coordination might be off and our ability to make quick decisions might be a little slow.2 Knowing that these are potential effects of a poor night’s sleep, consider modifying your workout to keep it safe. The table below provides an illustration of recommendations for workout modification. Sleep disruption, fatigue, and exercise Support yourself through physical activity and explore how best to encourage yourself through the barrier of fatigue. Chronic stress, whether emotional, social, or economic, can disrupt the circadian rhythm affecting your sleep/wake cycle. Some disruption is normal, but see your healthcare provider if you suffer from chronic sleep disturbances. It’s okay to modify your workouts to make it a little easier on yourself, maybe take away a little bit of the complexity of a workout. Research shows that a few physical performance indicators might decrease if we are fatigued, but it does not demonstrate that it should not be done.2,5-7 For example our ability to perform an agility task could be decreased if we’re tired because our coordination might be off and our ability to make quick decisions might be a little slow.2 Knowing that these are potential effects of a poor night’s sleep, consider modifying your workout to keep it safe. The table below provides an illustration of recommendations for workout modification. Research demonstrates that performing an aerobic activity could seem more challenging in a tired state, when compared to being well-rested.7 For example, when you’ve had a full night’s sleep, a particular run normally takes you 45 minutes, but when you haven’t had a full night’s sleep, this same run could take you 55 minutes and seem more difficult to complete. That is all right because you showed up regardless and you did it! You demonstrated your commitment to living an active life! It’s not a matter of a good workout once a month; it’s a matter of consistently being committed to living an active, safe lifestyle.

Before starting or making any changes to your exercise plans, please first consult your healthcare practitioner. References 1. NIH: National Institute of General Medical Sciences. Circadian Rhythms. https://www.nigms.nih.gov/education/pages/factsheet_circadianrhythms.aspx. Accessed September 24, 2019. 2. Romdhani M et al. Total sleep deprivation and recovery sleep affect the diurnal variation of agility performance: the gender differences. J Strength Cond Res. 2018. 3. Lack L et al. Chronotype differences in circadian rhythms of temperature, melatonin, and sleepiness as measured in a modified constant routine protocol. Nat Sci Sleep. 2009;1:1-8. 4. Stutz J et al. Effects of evening exercise on sleep in healthy participants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2019;49(2):269-287. 5. Orzeł-Gryglewska J. Consequences of sleep deprivation. International journal of occupational medicine and environmental health 2010;23:95-114. 6. Skein M et al. Intermittent-Sprint Performance and Muscle Glycogen after 30 h of Sleep Deprivation. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2011;43:1301-1311. 7. Temesi J et al. Does central fatigue explain reduced cycling after complete sleep deprivation. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45:2243-2253.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

|

Join Our Community

|

|

Amipro Disclaimer:

Certain persons, considered experts, may disagree with one or more of the foregoing statements, but the same are deemed, nevertheless, to be based on sound and reliable authority. No such statements shall be construed as a claim or representation as to Metagenics products, that they are offered for the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment or prevention of any disease. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed