|

By Molly Knudsen, MS, RDN There’s no doubt that antioxidants are good for health. Antioxidants have been in the public spotlight since the 1990s and have only gained attention over the years, basically reaching celebrity status. And that status has not wavered, especially as their role in immune health becomes increasingly known. Antioxidants and antioxidant-rich foods continue to trend and make headlines, most recently in the forms of matcha/green tea drinks, acai bowls, golden milk, or just good ol’ fashioned fresh fruits and vegetables. Antioxidants are here to stay not only because they’re found in delicious foods, but they also play a vital role in health by protecting the body against oxidative stress.1 What is oxidative stress? Everyone’s heard of oxidative stress, but what exactly does that refer to? Oxidative stress occurs from damage caused by free radicals. Free radicals are unstable molecules that have lost an electron from either normal body processes like metabolism, reactions due to exercise, or from external sources like cigarette smoke, pollutants, or radiation.1 Now electrons don’t like to be alone. They like to be in pairs. So do free radicals suck it up and leave one of their electrons unpaired? Nope. They steal an electron from another healthy molecule, turning that molecule into another free radical and, if excessive, wreak havoc in the body and its defense system. Immune cells are particularly vulnerable to oxidative stress because of the type of fat (polyunsaturated) that they have in their membrane.2 So high amounts of oxidative stress over time can be especially detrimental to immune system. What are antioxidants? Antioxidants are the heroes that can break this cycle. And there’s not just one antioxidant. Antioxidants refer to a whole class of molecules (including certain vitamins, minerals, compounds found in plants, and some compounds formed in the body) that share the same goal of protecting the body and the immune system against oxidative stress.2 But different foods contain different antioxidants, and each antioxidant has its own unique way of supporting that goal. 6 antioxidants for oxidative stress protection + immune health 1. Vitamin C Vitamin C is a powerful antioxidant that also contributes to immunity. It works by readily giving up one of its electrons to free radicals, thereby protecting important molecules like proteins, fats, and carbohydrates from damage.3 Vitamin C is a water-soluble vitamin, which means storage in the body is limited, and consistent intake of this nutrient is vital. Research shows that not getting enough vitamin C can impact immunity by weakening the body’s defense system.3 Vitamin C is found in many fruits and vegetables, including strawberries, bell peppers, citrus, kiwi, and broccoli. The benefits of vitamin C’s antioxidant capabilities are more than just internal. Benefits are also seen when a concentrated source of this antioxidant is applied to the skin. For example, topical vitamin C serums are often recommended by dermatologists and estheticians to help protect the skin from sunlight and address hyperpigmentation.4 2. Epigallocatechin 3-gallate (EGCG)

3. Glutathione Glutathione is a powerful antioxidant that the body actually makes internally from three amino acids (AKA building blocks of protein): cysteine, glutamate, and glycine.6 Not only does this antioxidant protect the body against oxidative stress, it also supports healthy liver detoxification processes.7 Glutathione levels naturally decrease with age, and lower glutathione levels in the body are associated with poorer health.8 Since it takes all three of those amino acids to form glutathione, ensuring that the body has adequate levels of all three is vital. Cysteine is the difficult one. It’s considered the “rate-limiting” step in this equation, since it’s usually the one in short supply, and glutathione can’t be formed without it.6 Cysteine contains sulfur, so foods like unprocessed meat, garlic, and asparagus are great choices to support cysteine levels. Like cysteine, the compound N-acetylcysteine (found in supplements and often labeled NAC) can also be used to support the body’s glutathione levels.6

5. Vitamin E

Vitamin E is a fat-soluble vitamin, meaning it’s best absorbed with fat. It acts as an antioxidant by stopping the production of free radicals from forming when fat is oxidized, or burned.10 Vitamin E is found in nuts and seeds (almonds, sunflower seeds, and hazelnuts) as well as green leafy vegetables. Vitamin E also plays a role in heart, eye, and cognitive health.10 6. Quercetin Quercetin is one of the most well-studied flavonoids, or plant compounds, typically found in onions, kale, broccoli, apples, and tea. Quercetin acts as a free radical-scavenging antioxidant, helps inhibit oxidative stress, and supports a healthy immune response.11 What’s the bottom line? Antioxidants are a crucial part to any healthful diet. They help protect the body from damage caused by oxidative stress and support immune function. There are many more antioxidants that are beneficial to health than those listed here. The best way to ensure that you’re getting enough antioxidants from the diet and supporting the antioxidants the body makes on its own is to consume a diet high in plants like fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, and legumes. References

0 Comments

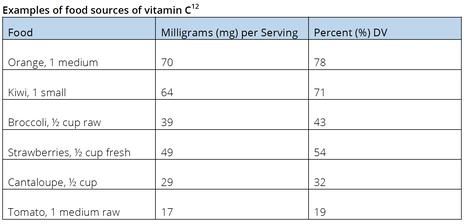

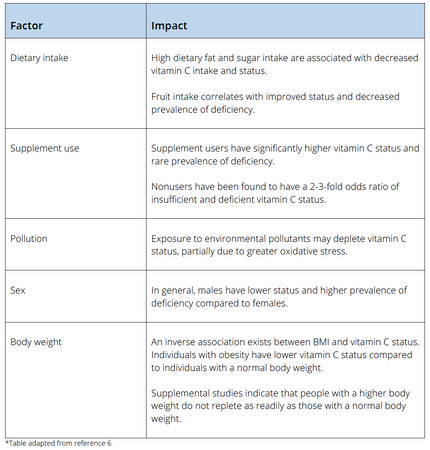

by Cassie Story, RDN Abstract: Although it was not identified and isolated until the 1930s, vitamin C has been known to protect against and treat certain disease states since the 18th century. Ask any health care practitioner to recall the first nutrient deficiency they learned about, and vitamin C will likely top the list. Images of sailors in the 1700s returning to shore with bleeding gums, fatigue, and even death due to a deficiency in this potent, water-soluble, antioxidant micronutrient likely come to mind. Ask any consumers what nutrient they should take during cold and flu season to help minimize their risk of infection, and once again, vitamin C will typically be their reply. For these reasons, vitamin C is arguably one of the most famous micronutrients. This post will dive into the role of vitamin C within the body and the potential health benefits of optimal intake and review considerations for its impact on the immune and respiratory systems. Function of vitamin C in the body Unlike most animals, due to the result of random genetic mutations, humans have lost the ability to synthesize ascorbate in our livers, making vitamin C an essential micronutrient.1 This important antioxidant serves many functions in disease prevention and optimal health status. Vitamin C is involved in protein metabolism and is required for the biosynthesis of certain neurotransmitters, as well as L-carnitine and collagen. It also serves as a cofactor for several enzyme reactions.2 Mild insufficiency, or hypovitaminosis C, has been associated with low mood, and more severe deficiency can lead to the clinical syndrome of scurvy, a condition that remains diagnosed in individuals today—and has played a role in global public health outbreaks.3,4 As vitamin C is a regenerative antioxidant, research continues to evaluate the impact of vitamin C and its role in reducing the destructive effect of free radicals. This may assist in the prevention of or delay in certain cancers, cardiovascular disease, and other conditions where oxidative stress affects human health.5 Not only does vitamin C have biosynthetic and antioxidant functions, it plays an important role in immune function and assists in the absorption of nonheme iron. Vitamin C absorption and status Vitamin C concentrations are tightly controlled within the body. Despite this, studies indicate that hypovitaminosis C and deficiency exist worldwide. Hypovitaminosis C is prevalent within certain populations in developed countries, including individuals with obesity, those who smoke, and people with low fruit and vegetable intake—and is the fourth leading micronutrient deficiency in the United States.6 Dietary intake is a primary factor in an individual’s vitamin C status. The amount consumed and frequency of consumption correlate well with plasma status and deficiency risk.6 Well absorbed in small quantities (i.e.: 200-400 mg at a time), through sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter-1 (SVCT-1), the enterocyte is rapidly saturated, and vitamin C is then transported, at varying concentrations, to several body tissues.7 Many organs have concentration-dependent mechanisms to retain vitamin C during situations where supply is low, namely brain tissue and adrenal glands.8 Plasma saturation occurs at a concentration between 70-80 µmol/L, although typical laboratory assessment methods prove highly susceptible to inaccuracies—leaving it challenging for many clinicians to assess accurate vitamin C status in their patients.8 Factors that impact vitamin C status6 Recommended intake and sources Population-based studies indicate that a majority of Americans meet the recommended dietary allowance (RDA), which is 90 milligrams (mg) per day for males and 75 mg per day for females, although ideal intake and serum concentrations have been a topic of debate for health experts around the world, and recommended values are not universal.9 A range of identified health benefits have been observed at higher intake levels. This has led a number of international agencies to increase their dietary recommendations, as the previous recommendations were based on the low level needed to prevent scurvy, which is estimated to be 10 mg per day.9 Despite its popularity among health care professionals and consumers, average US adult intakes are estimated to be 105 mg for males and 84 mg for females.10 While it is apparent that most individuals meet the RDA, many do not achieve the estimated optimal intake needed for its positive biological impact—which is speculated to be much higher, with many experts suggesting a daily intake of 200 mg for optimal health.11 Food sources Fresh fruit and vegetables are the main contributors of dietary vitamin C, with fruit intake correlating strongly with plasma vitamin C levels.6 Major contributors of vitamin C in the typical American diet are potatoes, citrus fruit, and tomatoes. Foods rich in vitamin C include oranges, kiwi, berries, papayas, mangos, melons, spinach, asparagus, and Brussels sprouts.12 Impact of vitamin C supplementation Supplemental use Five or more servings of fruits and vegetables per day can often lead to an optimal daily vitamin C intake of 200 mg, with special attention to one or two servings coming from a high-vitamin C source. This is not always possible, and taking supplements—in addition to dietary intake, can help to achieve and maintain optimal status.

Dietary supplement sources The majority of dietary supplements provide vitamin C in the form of ascorbic acid, which has an equivalent bioavailability to the naturally occurring ascorbic acid found in food sources.16 Other forms of supplemental vitamin C include mineral ascorbates, liposomal-encapsulated, or combination products. The upper limit has been set at 2,000 mg per day, due to the potential of diarrhea or other gastrointestinal (GI) effects, not due to a potential toxic impact. Buffered forms have been shown to help prevent GI distress and offer higher absorption than traditional ascorbic acid, possibly related to the presence of other minerals and amino acids. One study on 22 healthy subjects found that a buffered form of vitamin C improved absorption in healthy individuals by 18-25% when compared to ascorbic acid.17 Immune, inflammation, and respiratory impact Vitamin C appears to play a role in both prevention and treatment of respiratory and systemic infections by boosting several immune cell functions.18 Vitamin C status may be depleted by various disease states due to inflammatory processes and greater oxidative stress. During times of active infection, requirements for vitamin C increase with the severity of the infection—which requires significantly higher intakes to reach normal plasma status to make up for the added metabolic demands.6 Prophylactic prevention, on the other hand, advises that dietary intake is, at minimum, adequate. However, in order to achieve plasma saturation and optimize cell and tissue levels, doses of 100-200 mg per day are suggested.18 The role of vitamin C in immune defense and inflammation is multifactorial. It plays a role in inflammatory mediators by modulating cytokine production, decreasing histamine levels, and offering protection of key immune enzymes. Apoptosis, the necessary programmed cellular death of neutrophils, supports the resolution of inflammation and helps to prevent extreme tissue damage. Caspases are oxidant-sensitive, thiol-dependent, key enzymes in the apoptotic process. Vitamin C is thought to protect the caspase-dependent apoptotic process following the activation of neutrophils. Numerous studies have found weakened neutrophil apoptosis in patients with severe infection when compared to control groups. Animal studies have shown that administration of vitamin C greatly reduced the numbers of neutrophils in the lungs of septic animals.18 Cytokines, cell-signaling molecules secreted by certain immune cells, respond to infection and inflammation and can elicit a pro- or anti-inflammatory response. Vitamin C has been found to regulate systemic and leukocyte-derived cytokines in a multifaceted way. Preclinical, in vitro and animal studies have shown both positive and unfavorable effects of incubation with vitamin C. The effect of vitamin C seems to depend on the cell type and/or the inflammatory stimulant but overall appears to assist in normalizing cytokine generation.18 Following chemical exposure, natural killer (NK) cell function, as well as T and B cell function, decreases and can remain low for several weeks to months.17 Studies have shown enhanced immune function and improvement in NK cell function after oral doses of buffered vitamin C, as well as T and B cell function improvement following toxic chemical exposure. One study, of 55 subjects, used individualized dosing (60 mg/kg of body weight) of buffered vitamin C to evaluate the impact of high-dose vitamin C following a toxic chemical exposure and found that functional immune abnormalities can be restored following such an event.19 Allergies and the common cold Histamine, an immune mediator, is produced in response to pathogens and stress. Vitamin C depletion is associated with higher circulating levels of histamine. Intervention studies with supplemental oral vitamin C (range 125 mg–2 g/day) have found a decrease in histamine levels; however, they have been more impactful in patients with allergic symptoms compared to infectious diseases.18 The impact of vitamin C intake on common cold incidence has been an area of interest for the last 50 years.20 Meta-analyses have indicated that supplementation with 200 mg or more per day is effective in reducing the severity and duration of the common cold, and in individuals who have inadequate vitamin C status, vitamin C supplementation may decrease the incidence of the common cold. Thus, it appears that taking high-dose supplemental vitamin C daily during cold and flu season may reduce the risk of cold duration and severity.21 Respiratory impact Exposure to air pollution oxidants and tobacco smoke can alter the oxidant-antioxidant balance in the body and lead to oxidative stress.22 When vitamin C levels are insufficient, antioxidant defenses are impaired and can further compound the impact of oxidative stress within the body. Environmental oxidants can damage the respiratory tract lining fluid and increase the risk of respiratory disease. Vitamin C acts as a free-radical scavenger that can scavenge superoxide radicals and oxidant air pollutants—and its antioxidant properties offer protection to lung cells exposed to oxidants caused by various pollutants, heavy metals, pesticides, and xenobiotics.23 Vitamin C also plays a role in proper endothelial function, and deficiency has been associated in pulmonary arterial hypertension.24 Patients with acute respiratory infections have been found to have low plasma levels of vitamin C, and supplementation has been found to return plasma levels to normal and decrease the severity of respiratory symptoms. Beneficial effects of vitamin C supplementation on recovery of respiratory infections, including pneumonia, have been identified. Studies on hospitalized patients with pneumonia have found that supplemental vitamin C at a low dose (250-800 mg/day) reduced length of stay by 19% compared to those without vitamin C supplementation. Those that were given higher doses (500 mg–1.6 g per day) had an even greater reduction at 36%.18 It appears that low vitamin C levels seen during respiratory infections are both a source and a result of the disease. Respiratory health case study10 In a recent case study, a man in his 60s experienced shortness of breath and swelling of the legs associated with a frank vitamin C deficiency, which was attributed to a diet low in vitamin C and no supplemental intake. He was treated with supplemental vitamin C at 1,000 mg twice daily; his symptoms resolved after five months on this treatment plan.

Genetic variants Recent discoveries in genetic variants’ influence on vitamin C status have been found. Several single-nucleotide variants have been identified in the SLC23A1 gene, which encodes SVCT-1 and is responsible for the active uptake of dietary vitamin C and the reuptake of filtered vitamin C in the kidneys. In vitro data for this variant indicates a 40-75% decrease in vitamin C absorption from the gut and has been shown to present in 6-16% in those of African descent.25 A common variant of the hemoglobin-binding protein haptoglobin (Hp2-2) influences the metabolism of vitamin C. In vitro studies have found that this alters the ability to bind to hemoglobin and leads to an increase in oxidation of vitamin C.26 The Hp2-2 variant seems to have a greater impact on individuals with dietary intakes of less than 90 mg of vitamin C per day.27 Individuals with genetic variants that influence vitamin C status may require even higher dietary intakes. Luckily, high-dose vitamin supplementation has been found to amend certain gene-variant defects.28 Conclusion A majority of individuals would benefit from increasing fruit and vegetable intake to improve overall nutrition status, including vitamin C. Ensuring adequate intake of vitamin C through diet and with the use of supplementation is important for proper immune function and resistance to infections. This is especially critical for individuals with certain genetic SNPs or other lifestyle factors that may lead to a decline in vitamin C status. Citations

Cassie I. Story is a Registered Dietitian Nutritionist with 17 years of experience in treating metabolic and bariatric surgery and medical weight loss patients. She spent the first decade of her career as the lead dietitian for a large volume clinic in Scottsdale, Arizona. For the past seven years, she has been working with industry partners in order to improve nutrition education within the field. She is a national speaker, published author, and enjoys spending time with her two daughters hiking and creating new recipes in the kitchen! These days, it’s smart to be prepared for anything and ensure you and your family are well-stocked. It’s a good idea to take a regular inventory of every cabinet, from the kitchen cabinet to the medicine cabinet, making sure they are well-equipped and contain the items you prefer.

In addition to the standard bandages, hydrogen peroxide, and antibiotic ointment for minor cuts and scrapes, here are some ideas of what to stock and keep on hand in your medicine cabinet:

References:

By Molly Knudsen, MS, RDN Some things never change: The kids go back to school in the fall, the leaves change color shortly after, the holiday season approaches with increasing speed every year, and the cold or flu always seems to hit a household when the holiday season is happening. We know from experience that the common cold and flu hit the hardest when the weather gets the chilliest, but why is that? And can probiotics really help support your immune health so you can enjoy the holidays approaching? Are the seasons actually connected to health? According to science, it turns out that there are three main ways that the seasons may influence health. Environmental factors: One of the main predictors of disease rates across the globe is temperature.1 For example, evidence shows that both the northern and southern hemispheres have higher rates of seasonal respiratory viruses during their respective winter months.1 In addition, lower humidity levels (so dryer climates) are also associated with higher rates of these viruses.1 Humidity is believed to influence a virus’ stability and its ability to pass the infection on.1 Although these trends of virus prevalence are well-observed, more research is needed in this area as to why. Gene expression: Studies have found that 94 DNA transcripts, the basis for gene expression, show seasonal variability.2 This variability was found in transcripts involved with immune function.2 If the gene expression for immune function isn’t functioning optimally, that person may be more susceptible to these seasonal conditions. Human behavior: Cold weather usually changes people’s routines. As temperatures drop, people are likely to spend more time indoors and in confined areas, so viruses can spread easily by contact. Because people are inside more often and the sun is shining less, vitamin D levels tend to drop in the winter.1 Vitamin D is also believed to play a role in the immune response.1 How can you use nutrition as a tool to support your immune system this season?Common colds are so common that, on average, adults usally experience two to three per year, and kids often contract more, making colds the main culprit for missed days of work and school.3 Maintaining proper immune system function is especially important during this time. There are many simple habits you can start today to help keep the cold and flu at bay. Key vitamins and probiotics may also play a role in maintaining immune health. The age-old remedy of drinking orange juice for immune health may actually hold some validity. Oranges are high in vitamin C, and this vitamin has been shown to be a powerful antioxidant that contributes to the body’s immunity.4 Not getting enough vitamin C can impair immunity and weaken your body’s immune defense.4 Foods that are high in vitamin C include guavas, red bell peppers, tomatoes, and the ever-popular orange juice. Vitamin D also plays an important role in immune function. Vitamin D receptors are expressed on various immune cells and can modulate immune response.5 It is common for vitamin D levels to drop in the winter months, and oftentimes people may not even be aware if they are deficient in this nutrient.1 Low vitamin D levels are also associated with impaired immune function.5 Foods that contain vitamin D include fortified dairy products and plant-based dairy alternatives, fatty fish like salmon, and eggs. Some orange juices are also fortified with vitamin D. A staggering 70% of the immune system is located in the gut, and one not-so-intuitive habit to maintain your immune health, in addition to getting adequate amounts of these key vitamins, is to consider probiotics.6 Research shows that the probiotic strains Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM and Bifidobacterium lactis Bi-07 may help support immune function.7

These are the potential modes of action for how certain probiotics may support the immune response:8

References

The female-centric 411 on this essential nutrient

by Ashley Jordan Ferira, PhD, RDN Overview Vitamin D research and daily news headlines are ubiquitous. PubMed’s search engine contains over 81,400 articles pertaining to vitamin D.1 Information abounds on vitamin D, but the vetting and translation of that information into pragmatic recommendations is harder to find. Evidence-based takeaways and female-centric recommendations are crucial for healthcare practitioners (HCPs), their female patients and consumers alike. Women are busy, multi-tasking pros, so practical, personalized takeaways are always appreciated. In other words, women need the “411” on vitamin D. Merriam-Webster defines “411” as “relevant information” or the “skinny”.2 So for all of you busy women, here’s the skinny on vitamin D. Let’s explore common questions about this popular micronutrient. Q: Is vitamin D more important for younger or older women? A: All of the above. Vitamin D plays a critical role in women’s health across all life stages, from fertility/conception, to in utero, childhood, adolescence, adulthood, older adulthood, and even in palliative care. Vitamin D is converted by the liver and kidneys into its active hormone form: 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. This dynamic hormone binds nuclear receptors in many different organs in order to modulate gene expression related to many crucial health areas across the lifecycle, including bone, muscle, immune, cardiometabolic, brain, and pregnancy to name a few.3 Q: I am a grandmother. Are my vitamin D needs different than my daughter and granddaughter? A: Yes, age-specific vitamin D recommendations exist. As an essential fat-soluble vitamin, women need to achieve adequate levels of vitamin D daily. Age-specific Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDA) from The Institute of Medicine (IOM),4 as well as newer clinical guidelines from The Endocrine Society,5 provide helpful clinical direction for daily vitamin D intake and/or supplementation goals. The IOM RDAs4 are considered by many vitamin D researchers to be a conservative, minimum daily vitamin D intake estimate to support the bone health of a healthy population (i.e. prevent the manifestation of frank vitamin D deficiency as bone softening: rickets and osteomalacia): Infants (0-1 year): 400 IU/day Children & Adolescents (1-18 years): 600 IU/day Adults (19-70 years): 600 IU/day Older Adults (>70 years): 800 IU/day The Endocrine Society’s clinical practice guidelines5 recommend higher daily vitamin D levels than the IOM, with a different end-goal: raising the serum biomarker for vitamin D status [serum 25-hydroxvitamin D: 25(OH)D] into the sufficient range (≥ 30 ng/ml) in the individual patient: Infants (0-1 year): At least 1,000 IU/day Children & Adolescents (1-18 years): At least 1,000 IU/day Adults (19+ years): At least 1,500 – 2,000 IU/day Q: I am a health-conscious woman who eats a nutritious, well-rounded diet. I should not need a vitamin D supplement, right? A: Not so fast. Daily micronutrient needs can be met via diet alone for many vitamins and minerals. Vitamin D is one of the exceptions, which is why an alarming number of Americans (93%) are failing to consume the recommended levels from their diet alone.6-7 Very few foods are endogenous sources of animal-derived vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) or plant-derived vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol). Some natural vitamin D sources include certain fatty fish (e.g. salmon, mackerel, sardines, cod, halibut, and tuna), fish liver oils, eggs (yolk) and certain species of UV-irradiated mushrooms.8 In the early 20th century, the US began fortifying dairy and cereals with vitamin D to help combat rickets, which was widespread. For example, one cup (8 fluid ounces) of fortified milk will contain approximately 100 IU of vitamin D. Even though some food sources do exist, the amounts of these foods or beverages that an adult would need to consume daily in order to achieve healthy 25(OH)D levels (> 30 ng/ml) is quite unrealistic and even comical to consider. For example, you would need to toss back 20 glasses of milk daily or 50 eggs/day to achieve 2,000 IU of vitamin D! In contrast, daily vitamin D supplementation provides an easy and economical solution to consistently achieve 2,000 IU and any other specifically targeted levels. Q: I enjoy the outdoors and get out in the sun daily, so I should be getting all of the vitamin D that I need, correct? A: Vitamin D is a highly unique micronutrient due to its ability to be synthesized by our skin following sufficient ultraviolet (UV) B irradiation from the sun. Many factors can result in variable UV radiation exposure, including season, latitude, time of day, length of day, cloud cover, smog, skin’s melanin content, and sunscreen use. Furthermore, medical consensus advises limiting sun exposure due to its established carcinogenic effects. Interestingly, even when dietary and sun exposure are both considered, conservative estimates approximate that 1/3 of the US population still remains vitamin D insufficient or deficient.9 Q: What factors can increase my risk for being vitamin D deficient? Are there female-specific risk factors? A: Although the cutoff levels for vitamin D sufficiency vs. deficiency are still debated amongst vitamin D researchers and clinicians, insufficiency is considered a 25(OH)D of 21-29 ng/ml, while deficiency is < 20 ng/ml.5 Therefore, hypovitaminosis D (insufficiency and deficiency, collectively) occurs when a patient’s serum 25(OH)D falls below 30 ng/ml. The goal is 30 ng/ml or higher. Ideally, vitamin D intake recommendations4-5 and therapy are personalized by the HCP based on patient-specific information, such as baseline vitamin D status, vitamin D receptor single nucleotide polymorphisms and other pertinent risk factors. Common risk factors for vitamin D deficiency to look out for include: -Overweight/obesity -Older age -Regular sunscreen use -Winter season -Frequent TV viewing -Dairy product exclusion -Darker skin (more melanin) -Not using vitamin D supplements -Malabsorption disorders (e.g. bariatric surgery, IBD, cystic fibrosis) -Liver disease -Renal insufficiency -Certain drug classes: weight loss, fat substitutes, bile sequestrants, anti-convulsants, anti-retrovirals, anti-tuberculosis, anti-fungals, glucocorticoids -Lastly, additional female-specific risk factors to look out for include exclusive breastfeeding while mother is vitamin D insufficient (can result in infant being vitamin D deficient) and certain cultural clothing that covers significant amounts of skin surface area (e.g. hijab, niqab). Key Takeaways

Ashley Jordan Ferira, PhD, RDN is Manager of Medical Affairs and the Metagenics Institute, where she specializes in nutrition and medical communications and education. Dr. Ferira’s previous industry and consulting experiences span nutrition product development, education, communications, and corporate wellness. Ashley completed her bachelor’s degree at the University of Pennsylvania and PhD in Foods & Nutrition at The University of Georgia, where she researched the role of vitamin D in pediatric cardiometabolic disease risk. Dr. Ferira is a Registered Dietitian Nutritionist (RDN) and has served in leadership roles across local and statewide dietetics, academic, industry, and nonprofit sectors. Have you ever stood before the wall of vitamins at the drugstore or your healthcare practitioner’s office, wondering what you should take? Choosing supplements can be a daunting experience: Some boxes are orange. Some bottles are silver. Some contain iron, while others do not. Which one is right for you?

Start the selection process by getting specific about your particular stage of life. From young adulthood to the childbearing years and into menopause, each life stage may require greater emphasis on different nutrients to help your body get what it needs for optimal wellness. Young, ambitious, and carefree! Does this ring true for you? Women in their late teens or early 20s are going off to college, choosing a career path, and just beginning to explore adulthood. This is a time to be mindful of getting the appropriate nutrients you need to create a healthy foundation for the years ahead. Calcium. This mineral is important for women of all ages, but especially so in your 20s when bone mass reaches its peak. After this time, the risk of losing bone mass increases as a woman moves into her 30s and beyond.1 Taking a calcium supplement can help the body build bone, especially when paired with vitamin D3, which is known to enhance absorption of this vital mineral.2 Iron. Iron is important for young ladies, as menstruation is one of the ways this mineral is depleted from the body. In fact, menstruation increases the average daily iron loss to about 2 mg per day in premenopausal female adults,3 with excessive menstrual blood loss as the most common cause of iron deficiency in women.3 Baby, it’s you!The time of a woman’s life when she can become pregnant and have a baby is very special. It is also especially important to consider which nutrients are needed before conceiving and to ensure a smooth pregnancy and delivery. Folic acid. This vitamin (known as folate in its natural form) is needed before and during pregnancy. If you are considering getting pregnant, it is smart to increase folic acid intake before conceiving—there is strong evidence that taking folic acid prior to conception and during the first trimester of pregnancy can reduce the risk of neural tube defects of the brain, spine, or spinal cord by up to 70%.4Additionally, folic acid requirements are 5- to 10-fold higher in pregnant women than nonpregnant women,5 so get your folic acid going! Iron. Iron supplementation in pregnancy is often recommended. During pregnancy, the body’s iron requirements progressively increase until the third month.6 This is because more iron is needed for the growing fetus and placenta, as well as to increase your red blood cells.7 Calcium. Calcium is essential for fetal development, and this requirement increases during pregnancy (from 50 mg/day at the halfway point up to 330 mg/day at the end) and lactation.6 Iodine. During pregnancy, iodine is needed in the production of fetal thyroid hormones (the fetus’ thyroid begins functioning as early as 12 weeks in the womb!) and should be increased by about 50%.6 Vitamin D. Vitamin D (mostly vitamin D3, as it’s the predominant form in mom’s blood) is needed in the first stage of pregnancy, as it contributes to embryo implantation and the regulation of several hormones.6 Choline. Choline is an important nutrient for the health of women throughout their lifetime, and in particular during pregnancy. Choline is also vital for early brain development.8 The change of lifeAs your body progresses toward menopause, it produces less estrogen, opening up a world of change. It is during this time that certain nutrients can help support you in the management of symptoms like hot flashes and mood fluctuations, as well as help stave off concerns about bone mass loss. Calcium and vitamin D. In menopause, calcium remains a top nutrient to support the maintenance of bone mass. Bone turnover increases at this time, while the creation of new bone does not, which can lead to bone mass loss. Along with calcium, vitamin D is an important factor in helping to support bone health, which has been shown to help prevent bone mass loss in perimenopausal and menopausal women.9 Vitamin K and vitamin D. It has been shown that Vitamin D and K are both important nutritional factors in supporting mineralization and healthy structure of bones.10 Vitamin B12. When it comes to menopause, the B’s have it! Vitamin B12 plays a key role in energy metabolism, something we all need more of during menopause.11 Where to begin?Your healthcare practitioner is the best person to ask about which nutrients you may need. So get out of the vitamin aisle and in to see your doctor! This content is not intended as a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Individuals should always consult with their healthcare professional for advice on medical issues. References:

By Whitney Crouch, RDN & Kirti Salunkhe, MD

What is stress? Stress can be defined as a constellation of events, starting with a stimulus or stressor that causes a reaction in the brain leading to the stress response commonly known as the “fight-or-flight” reaction that can affect many body systems.1 Unfortunately, stress is a fact of life that we all experience at some time or another. Stressors that are acute, or short-lived, are often physical or physiological. Psychological or emotional stress is usually chronic in nature. The immune system and stress The immune system is made up of cells, tissues, and organs working together as the body’s defense mechanism to protect us from illness. Scientists say short-term stress (lasting from minutes to a few hours) may be beneficial for our immune health, as it stimulates immune activity and prepares us for possible periods of longer stress—a “fire drill” of sorts. However, chronic stress is actually harmful.2 White blood cells (WBC) are critical for the body’s immune response to foreign invaders. These cells are produced, and stored, in many areas of the body including the spleen, bone marrow, and thymus (a small gland found behind the sternum and between the lungs).3 There are two types of WBCs associated with the immune system: Phagocytes, which actively attack foreign organisms, and lymphocytes, which remind the body to recognize previous invaders and help destroy them.4 The main phagocyte is the neutrophil. Neutrophils primarily fight bacteria and infections. The main lymphocytes are the B lymphocytes or B-cells and T lymphocytes or T-cells. B-cells start out and mature in the bone marrow. T-cells start out in the bone marrow but mature in the thymus. These two cell types are the “special ops” of the immune system and have specific functions. B-cells make antibodies to fight bacteria and viruses and T-cells directly attack invading organisms.4 Acute stress and the immune response One of the most familiar reactions to acute stress is the “fight-or-flight” response. This physiological reaction usually occurs during an emergency or a fearful mental or physical situation.3 When a threat is perceived, there is a release of hormones to prepare you to either stay and deal with the threat or to run away to safety. It represents choices our ancient ancestors made when faced with dangerous situations. Nowadays, it’s more likely those dangerous situations are ones leading to a wound or infection, but our body reacts the same way.3 During periods of short-term stress, our sympathetic nervous system releases “stress hormones:” epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline), as well as corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), adrenocorticotropin (ACTH), and cortisol from the adrenal glands.3 These work together to prepare the body for “fight-or-flight” by increasing alertness, focusing the mind, elevating heart and breathing rates, as well as increasing blood flow to skeletal muscles and brain.4 Interestingly, research has shown acute stress activates the immune system. Immune activation is critical to respond to immediate demands of a stressful situation that may lead to a wound or an infection. Acute stress triggers immune cells and stimulates production of proteins known as cytokines. The two major types of cytokines are: pro-inflammatory cytokines and anti-inflammatory cytokines. The pro-inflammatory cytokines process the pain often found with inflammation; the anti-inflammatory cytokines work by controlling, or limiting, the spread of inflammation. Both are necessary for normal healing.3 While acute, or short-term, stress acts as an “immune stimulator,” readying the body’s immune system for an adverse situation, situations involving long-term or chronic stress actually suppress and dysregulate the body’s immune responsiveness, leading to illness and poor outcomes.3 Chronic stress and the immune response Just as we all have differing genetic and biochemical composition, we also have varying perceptions of stress and individual responses to how we process and cope with it.5 Occasionally, there can be a crossover between the mind and body, as in the “fight-or-flight” response. A mentally stressful situation may require a physical response or action, but what about those psychological or emotional stressors that may be difficult but don’t actually pose any pressing physical dangers? Stressors related to pressures of a work project requiring focused concentration over long days and nights, or the continual emotional drain from a difficult relationship or other similar circumstance? Studies have shown prolonged mental stress can adversely affect regular lifestyle routines, including decisions we make about sleep, nutritional intake, and exercise and can even persuade us to use poor judgement regarding alcohol and drug intake.5,6 These studies have also shown the adverse effects (acute and chronic) that mental and emotional stress places on physical health and wellbeing and have been directly linked to suppression of the immune system.5 How acute mental stress affects physical health was seen in a recent study of college students during their final exams.7 To understand the link between mental stress and changes in blood biomarkers, researchers took blood samples and administered questionnaires about anxiety and depression to 24 college students during finals week. Baseline values had been established by prior blood draws and questionnaires completed midsemester. When compared to baseline levels, during finals week, there were elevations in pro-inflammatory cytokines along with increased reports of anxiety and stress.7 Other studies have noted increased stress can lead to prolonged wound healing time with reduced levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines and increases in pro-inflammatory cytokines.6 Multiple studies have evaluated the immune response in conditions of long-term and emotional stress. These conditions are similar to those found with caregiving of an ill or elderly relative, experienced after a difficult divorce and have even been reported as related to loneliness.7-9 Findings from these studies showed links between emotional stress and increased risk for viral illness, reemergence of latent viruses (Epstein-Barr, herpes simplex, and cytomegalovirus), and onset of autoimmune disease.5,10,11 Other studies have shown long-term psychological stress was linked to detrimental cardiovascular health12-14 as well as increased risk for immunologic conditions including inflammatory bowel disease, allergies, atopic dermatitis, and celiac disease.15-18 Even the most vulnerable members of the population, our children, can be affected by psychological stress that results in a reduced immune response. Investigators evaluated children who had a history of recurrent colds and flu and reported higher levels of psychological stress. The data demonstrated the children had reduced salivary immunoglobulin ratios (IgA/albumin). A reduction in this ratio supports a potential link between reduced immune function with a greater susceptibility to colds and flu.19 Lifestyle approaches to stress management While the effects of stress can be useful on some occasions, adverse effects of stress can play a role in both acute and chronic illness. While there are a number of strategies that come into play with stress management, evidence supports the benefits of lifestyle modification and improved dietary or nutritional intake as a part of a comprehensive strategy. Recommended lifestyle modifications:

This information is for educational purposes only. This content is not intended as a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Individuals should always consult with their healthcare professional for advice on medical issues. References:

Whitney Crouch, RDN, CLT Whitney Crouch is a Registered Dietitian who received her undergraduate degree in Clinical Nutrition from the University of California, Davis. She has over 10 years of experience across multiple areas of dietetics, specializing in integrative and functional nutrition and food sensitivities. When she’s not creating educational programs or writing about nutrition, she’s spending time with her husband and young son. She’s often found running around the bay near her home with the family’s dog or in the kitchen cooking up new ideas to help her picky eater expand his palate. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

|

Join Our Community

|

|

Amipro Disclaimer:

Certain persons, considered experts, may disagree with one or more of the foregoing statements, but the same are deemed, nevertheless, to be based on sound and reliable authority. No such statements shall be construed as a claim or representation as to Metagenics products, that they are offered for the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment or prevention of any disease. PAIA Manual |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed